1. Budget and Nutrition Schemes

Hunger and Malnutrition ‘Emergency’

India’s rulers may be claiming that the country is heading towards becoming a global superpower, but what is for sure is that its hunger levels are amongst the worst in the world. The Global Hunger Index (GHI), a multidimensional statistical tool designed to comprehensively measure and track hunger globally and by country and region, ranked India a very low 94 out of 107 countries for which sufficient data was available to calculate the GHI scores in 2020. It placed India in the ‘serious’ hunger category; and ranked it much behind even its poor neighbours – Bangladesh, Pakistan and Nepal.[1]

India is also at the epicentre of a global stunting crisis, due to child malnutrition. Data from the National Family Health Survey–4 (2015–16) had shown that 38.4% of children under the age of five are stunted (low height for age, indicating chronic malnutrition), and 35.7% are underweight (low weight for age, indicating both chronic and acute malnutrition). More recently, data from National Family Health Survey–5 (2020) was released for 17 states and 5 Union Territories (data for U.P., M.P. Tamil Nadu, Rajasthan, Punjab, Jharkhand and Odisha are not yet out). The survey was conducted before the pandemic struck. The data shows that in most of the states, the nutritional status of children had worsened over the last five years. If the all-India figures too show the same results, this would reverse decades of improvements.[2]

Under /mal-nutrition severely stunts intellectual, emotional and physical growth. Studies also show that the effect of malnutrition is most acute in the age group from 0 to 3 and this cannot be mitigated in one’s adult life; in other words, both body growth and brain development are permanently adversely affected.

Clearly, for a country facing such a hunger and malnutrition crisis, this should be The Most Important crisis facing its policy planners, and they need to urgently address it.

The country has more than enough foodgrains to tackle this hunger crisis – in September 2020, foodgrain stocks were up to 70 million tonnes (excluding un-milled paddy), which is enough to ensure that no one went hungry.[3] Then why is the country facing such a Hunger Emergency?

i) Food Subsidy

The most important programme in the country to tackle this hunger and malnutrition crisis facing the country is the food subsidy programme, wherein the government provides essential food and non-food items to the poor at subsidised rates through the public distribution system (PDS). This food subsidy programme is mandated under the National Food Security Act (NFSA), passed by the Parliament in 2013.

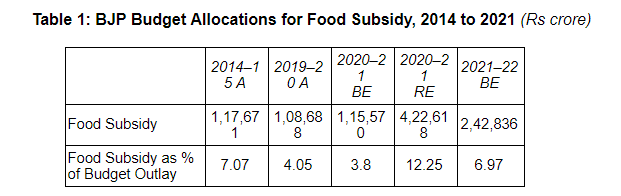

While the BJP, when it was in opposition, had criticised the NFSA as inadequate and called for universalisation of food security, after it came to power, the food subsidy both as a percentage of budget outlay and as a percentage of GDP has declined in the first seven budgets of the Modi Government (2014–15 A to 2020-21 BE) (see Table 1). The food subsidy bill had been slashed so massively that allocation under this head as a percentage of budget outlay had fallen by half over these seven budgets – despite the worsening of the hunger crisis!

That is the reason for the worsening hunger crisis – the refusal of the Modi Govt to universalise the PDS and increase allocation under it, so that all the poor can have enough to eat!

During the pandemic, with a very inadequate relief package causing widespread distress, the government was forced to increase its food subsidy budget to provide 5 kg of foodgrains free to all those covered by the NFSA. Consequently, the food subsidy budget for 2020-21 RE increased by more than 3 times, to Rs 4.22 lakh crore, as compared to the budgeted Rs 1.16 lakh crore.

With the government now claiming that the economy is returning to normal – even though the GDP figues belie this claim, as we have explained in Part 1 of this article – in this year’s budget, the government has cut its food subsidy budget by nearly half, to Rs 2.42 lakh crore. A part of this money is also likely to be used to clear arrears due to the Food Corporation of India and other agencies. While this figure for 2021 BE looks much larger than the 2020 BE, as the above table shows, the amount as a percentage of budget outlay is actually less than for 2014 A. Moreover, as we have explained in Part 2, the government’s revenue collections are in all likelihood going to much less than the budgetary estimates, and so it shouldn’t be surprising if the budget actuals show that actual spending under this head is much less than this budgeted amount.

The preparations for a further cut in food subsidy have begun. The government’s neoliberal think tank, the NITI Aayog, has recommended that the percentage of population covered under the National Food Security Act be reduced from 75% to 60% in the rural areas, and to 40% from the current 50% for the urban areas.

In the medium term, the government is planning to end procurement of foodgrains and eliminate the public distribution system, and replace it by cash transfers to the poor, which can then be suitably wound down to reduce the food subsidy bill even more (just like has happened for cooking gas). That is one of the aims of the three farm bills that the farmers are agitating against. Which is why the agitation of the farmers needs to be supported by all the people of the country.

How much would Universalisation and Expansion of PDS Cost?

Whereas what is needed for tackling the ‘hunger and malnutrition crisis’ gripping the country is that the PDS be universalised, and expanded to include other food essentials like pulses and edible oil!, In an article published in an earlier issue of Janata, we have shown that the total increase in food subsidy required for universalising the PDS and providing all citizens 35 kg of wheat /rice and 5 kg of millets per household per month will cost the exchequer an additional Rs 85,000 crore at the most (calculation made for 2017–18). Additionally, if the government decides to distribute 2 kg of pulses and 1 kg of edible oil to all families through the PDS, even assuming a subsidy of Rs 50 per kg for both these food essentials, that would cost the exchequer at the most Rs 40,000 crore. This means that universalising and expanding the PDS would only lead to a total increase in the food subsidy bill of Rs 1.25 lakh crore.[4] That was calculated for 2017-18. So, assuming inflation of 8% per annum, this amount today would be Rs 1.70 lakh crore (for 2021-22).

That is not much, for a government which can afford to push the RBI and public sector banks to write off bad loans totalling Rs 1.15 lakh crore in the first three quarters of 2020-21 (and Rs 2.34 lakh crore in 2019-20)[5] – most of the beneficiaries would obviously be big corporate houses. It is because of such subsidies that the wealth of India’s billionaires soared during the pandemic, while the poor lost their jobs and starved because of the government’s unwillingness to give a decent relief to the poor.

ii) Other Nutrition Schemes

The previous governments had put in place several “nutrition” schemes oriented towards pregnant women and children. While the funding for them was inadequate, at least they attempted to address the problem. Most of them are included under the umbrella of Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS), and include Anganwadi services and the Maternity Benefit Programme (MBP), apart from some other smaller schemes. Another important scheme that is also nutrition-oriented, but comes under the Human Resource Development Ministry, is the Mid-Day Meal Scheme for school children.

Just like for the food subsidy programme, the Modi Government has been reducing the Central allocations for these other nutrition schemes too. Let us first take a look at what happened during the first seven budgets of the Modi regime.

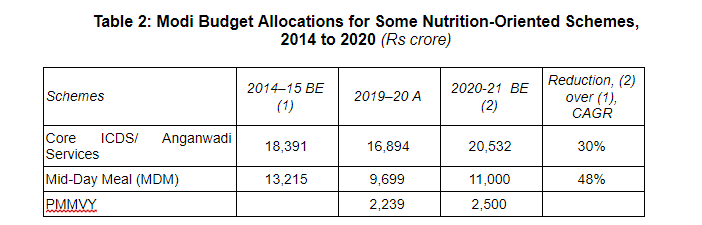

Anganwadi Services: This is probably the most important of these nutrition schemes. It is a programme aimed at providing health, education and supplementary nutrition to mothers and children below 6 years of age. During the first seven Modi Budgets, allocation for Anganwadi services were cut in real terms by one-third. This huge reduction has been made, despite a damning Niti Ayog Report of 2015 showing that around 41% of the Anganwadis have inadequate space, 71% are not visited by doctors, 31% have no nutritional supplementation for malnourished children and 52% have bad hygienic conditions.[6] The reduction in budgetary allocations since then only means that the conditions must have only got worse.

The budget cuts are indicative of our ruling regime’s complete insensitivity towards the 5 crore children in the country who are malnourished and the more than two crore pregnant women and lactating mothers. That is the true essence of the Hindu Rashtra that the BJP is seeking to usher in the country!

Mid-Day Meals Scheme: This is another important nutrition programme to combat the huge malnutrition levels among children in the country; an additional objective is to improve school enrolment and child attendance in schools. But the government is not willing to allocate a decent amount for providing one nutritious meal a day to our children, despite the fact that more than one-third of the country’s children under five—about 47 million souls—suffer from stunting. During the first seven budgets of the Modi Govt (2014-15 to 2020-21), allocation for this scheme has been cut by nearly half (see Table 2).

Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana: The NFSA, passed just before the 2014 elections, had mandated this programme for the entire country, and gave an allowance of Rs 6,000 per month to all pregnant and lactating mothers. But after winning elections, the BJP delayed the implementation of this programme for 3 years. After intense pressure from activists, the implementation of this scheme was finally announced by FM in his 2017 budget speech.

It is a very insensitive government in power. Even after announcing a full roll-out of the scheme, the finance minister included so many conditionalities, such as that women can avail of this allowance only if they deliver in hospitals, that they have ended up excluding more than 50% of the country’s women from this scheme. But they are the ones who need these maternity benefits the most, as they include women from the poorest sections of the population, belong to Dalit and Adivasi communities, and live in the remotest areas of the country. They are unable to deliver in hospitals or vaccinate their children, because of the terrible state of government health services in the country. Instead of focussing on improving facilities in government hospitals, and making hospitals more accessible for the poor (by improving ambulance facilities), the suit-boot sarkar’s FM/PM have put the blame on the victims of our dismal public health system, and excluded them from receiving maternity benefits!

Under this guise, the FM has been allocating only around Rs 2,500 for this scheme, whereas a genuine allocation for this scheme would require an allocation by the Centre of at least Rs 9,700 crore per year (assuming Centre–State sharing to be in the ratio of 60:40)[7]

Let us now take a look at the allocations for these schemes in the 2020-21 RE and this year’s budget.

Nutrition Schemes and 2021-22 Budget

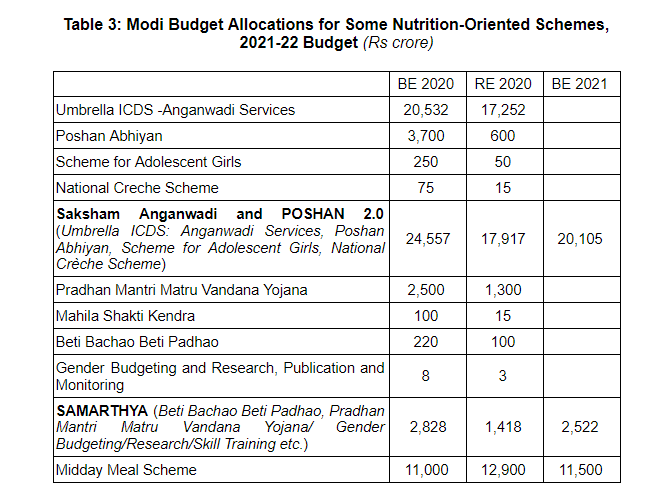

During the lockdown, the implementation of important nutrition schemes like the Anganwadi services and Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana (PMMVY) suffered greatly, because of the closing of the Anganwadi centres. The revised estimates for Anganwadi services shows a reduction of 16%, while that for PMMVY is barely half of the allocation (Table 3).

In the 2021-22 budget, ICDS and PMMVY have been clubbed with other schemes, but comparing like with like, it is clear that both programmes have been undermined. This year, Anganwadi services have been clubbed with three other schemes, and yet the combined allocation for all four is only Rs 20,105 crore, which is less than the allocation for Anganwadi services in last year’s BE, of Rs 20,532 crore. Similarly, allocation for PMMVY in last year’s BE was a very inadequate Rs 2,500 crore; this year, after clubbing PMMY with three other schemes, the combined allocation is only Rs 2,522 crore. (Table 3)

The allocation for Mid-Day Meals scheme continues to be a low Rs 11,500 crore – which is even less than the allocation in 2014-15 BE. (Table 3)

Table 3: Modi Budget Allocations for Some Nutrition-Oriented Schemes,

2021-22 Budget (Rs crore)

2. Budget and Pensions

More than 90% of the people in India work in the informal sector. These workers do very hard, back-breaking work, and so by the time they become old, their bodies are broken and they suffer from many diseases. Therefore, apart from providing them universal and free health care facilities—not just hospitalisation but free outpatient facilities too—it is essential that the government provides them a decent old age pension too.

Presently, the main programme for providing social security to the poor (including the disabled and widows) and especially those working in the unorganised sector is the National Social Assistance Programme (NSAP).

The budget allocation for this vitally important program for the rural and urban poor is nothing less than scandalous.

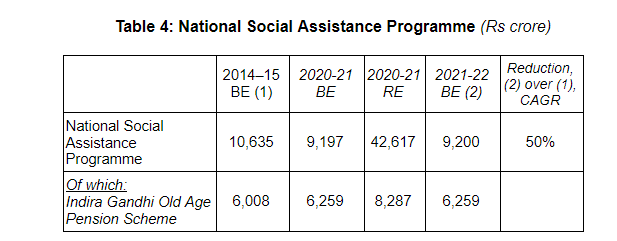

The budget allocation for this program in the BE last year was less than the allocation made for this programme in the first budget of the Modi Govt in 2014, implying a cut of 45% in real terms. Then, the lockdown hit the economy, and the government was forced to give out a relief package. Among the few things it did was a direct transfer of Rs 1,500 to all women account holders of Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana (a total of 20 crore women). The total allocation for this as seen in the 2020-21 RE is Rs 30,957 cr, because of which the allocation for NSAP has gone up to Rs 42,617 cr in the RE. But the very next year, that is, in this year’s BE, the allocation for NSAP has gone down to Rs 9,200 cr, the same as the BE for last year, which implies a cut of 50% as compared to the allocation in 2014-15 BE. (Table 4)

Table 4: National Social Assistance Programme (Rs crore)

The total number of poor in country – even according to the government’s convoluted statistics – is 36 crore. With an annual allocation of Rs 9200 crore for them under the NSAP, it works out to a social assistance of Rs 250 per person per year—a princely sum indeed!

The most important scheme under this program is the Indira Gandhi Old Age Pension Scheme, under which the Central Government provides a ridiculously low pension of Rs 200 per month to old people above the age of 60. [State governments are supposed to add to this by making their own contribution. While some states provide a decent additional amount of Rs 1,800 per month (Goa, Tamil Nadu and Delhi), most states provide an additional amount of only Rs 200–300 per month for a total old age pension of Rs 500 per month or less.] This pension amount of Rs 200 has remained unchanged since 2007—applying a deflation rate of 8% per annum means that its real value has fallen to less than Rs 90 today! Even this low amount is given to only those citizens below the poverty line; as is well known, a very large number of the poor do not have BPL cards, and so are deprived of this tiny amount too!

References

1. “Global Hunger Index 2020: India ranks 94 out of 107 countries, under ‘serious’ category”, 19 October 2020, https://indianexpress.com.

2. “NFHS 5 Report Highlights: Malnutrition In Children Has Worsened In Key States Of India, Experts Say We Need To Rethink Our Nutrition Plan”, 5 January 2021, https://swachhindia.ndtv.com.

3. Dibyendu Chaudhuri , Parijat Ghosh, “Global Hunger Index: Why is India trailing?”, 23 October 2020, Down to Earth, https://www.downtoearth.org.in.

4. Neeraj Jain, “For a Universalised Public Distribution System”, Janata Weekly, August 27, 2017, https://janataweekly.org.

5. “Banks Wrote-off Rs 1.15 Lakh Crore in First Three Quarters of FY21: Anurag Thakur”, 9 March 2021, https://thewire.in.

6. Sourindra Mohan Ghosh, Imrana Qadeer, “An Inadequate and Misdirected Health Budget”, February 8, 2017, https://thewire.in.

7. Dipa Sinha, “Budget 2017 Disappoints, Maternity Benefit Programme Underfunded, Excludes Those Who Need It the Most”, February 3, 2017, http://everylifecounts.ndtv.com.