1. Budget and Education

Education is fundamental to human as well as societal development. Which is why in all developed countries, governments have taken the responsibility of providing Free, Equitable and Good Quality school education to All their children (the private sector invests only for profit).

Unfortunately, in India, public school education is in a terrible state. This is borne out by the extremely inadequate number of teachers in our schools. According to government data:

- more than 70 percent primary schools had three or less than three teachers; and

- 57 percent of all primary schools had three or less than three classrooms;

- implying that a single teacher is teaching two or three different classes at the same time in a single room in a majority of the primary schools in the country! (The situation is equally bad in the senior-level schools in the country.)[1]

At the same time, because of low level of government spending, a majority of our schools lack even basic infrastructure like electricity and computers.[2]

Therefore, it is not surprising that the quality of education in our schools is so bad that nearly half the children in Class 5 are not able to read Class II–level text, and nearly three-fourths (72 percent) cannot solve a simple division problem.[3]

It is because of our government’s unconcern for educating our children that the 2011 Census figures, the most reliable data source in the country, show that of the 20.8 crore children between the age of 6–13 in the country, 3.2 crore or 15.4 percent children have never attended any school![4] That is huge.

And of those who enrol in school in Class I, a large number don’t even complete elementary school. The drop-out rates at the various levels are:[5]

- Drop-out rate at the primary level is 15.5 percent;

- Drop-out rate at the elementary level is 30 percent (this means that of 100 children enrolled in Class 1, only 70 reach Class 8).

- Drop-out rate at the secondary level is a huge 47.3 percent.

Reason for this terrible situation is, that government expenditure on school education is very low.

The BJP, led by Narendra Modi, promised to rectify this situation and increase spending on education to 6% of GDP on education – as recommended by the Kothari Commission on Education several decades ago. This too, like all its other election promises, has turned out to be a jumla. During the eight budgets presented by the Modi Government, school education has been sharply cut – the first time any government has done this after Independence:

The school education budget this year is even less than the allocation for education made in the first Modi budget. Taking inflation at an average of 8% per year, the reduction is a whopping 42% in real terms!

As compared to the budget allocation for last year, the school education budget has been cut by 8.3% – which means an effective cut of nearly 15% in real terms.

The reason for this huge budget cut for school education is simple: the BJP wants to privatise school education completely. For this, the strategy adopted is simple: ruin the quality of government school system by cutting the funding of school education and keeping teaching posts vacant; children will automatically exit government schools, and those who can afford it will join private schools. The consequence: more than 2 lakh government schools have closed down till date.[6]

If we look closely examine the education budget, another skewed priority of the government gets revealed. The National Education Policy (NEP) of the Modi Government that was passed this year called for a doubling of government expenditure over the next 10 years, starting from this year. While that is not seen in this year’s education budget, nor is it even mentioned in the FM’s budget speech, the FM does make a mention of “strengthening of 15,000 schools” in line with the NEP. That is only about 1% of the total schools in the country. Are the others not part of the NEP? And which are going to be these 15,000 lucky schools?

While not expressly mentioned in the budget speech, a closer look at the budget document reveals which schools the FM is talking about. The allocation for Kendriya Vidyalayas has been increased, from Rs 6,438 crore in 2020-21 to Rs 6,800 crore this year; and that for Navodaya Vidyalayas has gone up from Rs 3,480 crores to Rs 3,800 crores. But these schools already receive preferential treatment with much higher expenditure per student, a full complement of teachers and good infrastructure. It is the lakhs of other schools that require the extra support. If of the reduced school education budget, allocation for these more elite schools is being increased, it only means that the allocation for the lakhs of other schools has fallen even more than the 15% cut in the overall school education budget.

Business of Higher Education

For a country aspiring to be an economic superpower, the state of higher education is dismal. Barely 20% of children in age group 17-23 are in any kind of higher education degree or diploma course; this proportion is above 60 for developed countries; for many countries, this ratio is above 70.[7]

An important reason for this is the accelerating privatisation and commercialisation of higher education in the country, as a part of the neoliberal reforms being implemented in the country at the behest of international capital. Private higher educational institutions are all for-profit institutions; therefore, very few students can afford their fees. And so, two decades after the reforms began, by 2011–12, private higher educational institutions (including both degree and diploma institutions) accounted for more than two-thirds of all higher educational institutions in the country, and for nearly 60% of student enrolment.[8]

The situation has worsened under the Modi regime. In the eight Modi budgets presented so far, the Centre has cut its spending on higher education (2021-22 over 2014–15 BE) by 19% in real terms assuming inflation of 8%) (see Table 1). This year’s higher education budget is marginally less than last year’s budget estimate, implying a reduction of around 10% in real terms.

Because of this, most government funded colleges are starved of funds and so, to meet their expenses, are being forced to increase student fees using all kinds of excuses. Consequently, studying in government funded educational institutions too is becoming unaffordable for students from poor families.

Even within the limited higher education budget, most of the funding is going to elite government institutions like the IITs and IIMS:

- Allocation for the University Grants Commission, that regulates the higher educational institutions in the country and provides grants to more than 10,000 institutions, has been halved in the eight Modi budgets, from Rs 8,978 crore in 2014–15 BE to just Rs 4,693 crore in 2021-22 BE.

- Likewise, allocation for the All India Council for Technical Education, the regulator of engineering education in India, has remained dismally low during all the 8 Modi budgets and is a lowly Rs 416 crore in the 2021-22 BE.

- In contrast, more than 50% of the higher education budget has been allocated for the elite higher educational institutions, that is, the IITs, IIMs, IISERs, NITs, IIITs, IISc, and the Central Universities. The total allocatin for them is Rs 21,600 crore, which amounts to 56% of the total higher education budget!

Cogs in the Corporate Wheel

The corporate-fascist alliance ruling the country is very clear in its outlook. There is no need to educate the young – only then can they be transformed into mindless automatons in the service of virulent Hindutva. So the overall budget for education has been cut by one-third in seven years of Modi rule.

But the corporates also need good quality engineers and managers. And so, despite this cut in allocation for education, the spending on elite schools and engineering / management colleges is being increased.

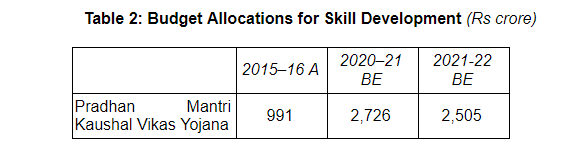

At the same time, the corporates also need skilled workers for their assembly lines. For this, the youth must be trained – not educated – so that they can become cogs in the corporate wheel. For this, the Modi regime has opened a separate ministry, the Ministry of Skill Development, and allocation for the most important program under this, the Pradhan Mantri Kaushal Vikas Yojana, has tripled in the six years since it was launched.

2. Budget and Health

India is the disease capital of world. Lakhs of people die every year of entirely curable diseases, such as gastro-enteritis and tuberculosis. India’s infant mortality rate is the worst among all developing countries.

The reason for this appalling situation is India’s abysmal public health care system, which is in an abysmal shape because of complete government neglect. India’s public health expenditure is among the lowest in the world: India spends barely 1.5% of its GDP on healthcare (both Centre and states combined). India’s public health expenditure is lower than even most low income countries; the world average is 6%.[9] This is admitted by this year’s Economic Survey too: it states that India ranks 179 of 189 countries in prioritisation of health in government budgets.

Consequently, India’s public health infrastructure is in poor health. To give just one example, in rural areas, the main hospital is called the community health centre (or CHC). It is supposed to have 4 specialist doctors – surgeon, physician, gynecologist/obstetrician and pediatrician. While as per government standards, the country is supposed to have 7800 CHCs, only 5600 exist (that is, 70%). Even more distressing is the admission by government statistics that the working CHCs suffer from a 80% shortage of doctors: they are supposed to have 5600 x 4 = 22400 doctors, but have only 4000! Nearly 4700 CHCs have operating theatres with no surgeons to man them![10]

The Economic Survey 2020-21 admits that India currently ranks 145 out of 180 countries in quality of and access to healthcare.

Our public health services were therefore totally inadequate to face the challenge of the corona pandemic. So, when the lockdown began and the relief package was announced, it was expected that the government would at least double its health expenditure, to improve our public health services (even then, it would have increased to only 3% of the GDP, half the world average). But an unconcerned government just locked down the country and did nothing else. Budget figures show that total increase in the budget for Department for Health and Family Welfare during 2020-21 (Revised Estimate over Budget Estimate) is a just Rs 13,854 crore (from Rs 65,012 cr to Rs 78,866 cr.) – a shockingly low amount considering the scale of the health crisis.

This neglect of our public health services is an important reason why the corona pandemic spread rapidly across the country, causing more than a lakh deaths and devastating the economy. (If the deaths per million is lower than the developed countries, it is not because of our health system, but because the virus had a much lower health impact in countries of South Asia – discussing this is beyond the scope of this essay.) At the same time, because of our very inadequate public health services, they got so overstretched dealing with corona cases that during the first few months of the lockdown, all regular public health services – including immunisation and maternity care – totally collapsed. Surveys have yet to be done to fully capture the impact of this on overall health status of the people, including the spread of diseases such as tuberculosis.

2021 Health Budget

In the very beginning of her 2021 budget speech, as if to rectify this situation, the Finance Minister made the grand announcement that “investment on Health Infrastructure in this Budget has increased substantially…. The Budget outlay for Health and Wellbeing is Rs 2,23,846 crore in BE 2021-22 as against this year’s BE of Rs 94,452 crore, an increase of 137 percentage.”

An increase of nearly 2.5 times: the announcement was greeted with cheers by the treasury benches, and headlined by the media next day.

But like all Modi Government announcements, a closer examination reveals that this was yet another BIG LIE!

The Finance Minister conjured up this huge outlay of Rs 2.24 lakh cr for healthcare by using a broad definition of “health and well being” (see Table 3). She included in this, apart from the allocation for Ministry of Health and Family Welfare and Ministry of AYUSH (which together constitute the actual health budget of the government): (i) an allocation of Rs 35,000 crore for the unavoidable vaccination drive (actually, this is a very inadequate allocation); and (ii) proposed spending on a range of other programs. The latter includes: (a) The finance commission’s mandated grants to the States for water and sanitation and health of Rs 49,214 crore. These in no way can be considered discretionary and enhanced expenditures on the part of the Centre, so it is a complete fraud to include them in a so-called “health and well-being” budget of the Centre. (b) An enhanced allocation for the Department of Drinking Water and Sanitation, from Rs 21,518 cr in 2020 BE to Rs 60,030 cr in the 2021 BE. This increase seeks to provide safe and adequate drinking water through individual household tap connections in rural and urban areas. While safe drinking water provision does help improve health and well being, and this increase is welcome, it cannot be counted among core expenditures on health. It is the budget expenditure of an entirely different ministry.

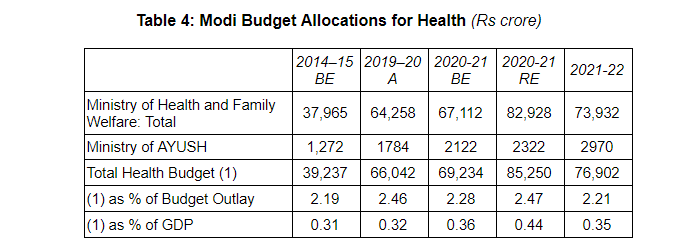

The core health budget, the budget allocation for Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (first two rows of Table 3) plus Ministry of AYUSH, is actually less than the 2020-21 RE (see Table 4)! This allocation increased during the pandemic, as shown in the table, by 23.6%, but has been cut in the 2021-22 BE. While the allocation for this year is more than last year’s BE by 10% (barely enough to beat inflation), it is less than last year’s RE by 10.8%. So much for the Modi Government’ concern for health and well-being!

Therefore, the Centre’s expenditure on health continues to languish at just 0.35% of GDP. This has remained so, despite the Modi Government promising in its National Health Policy (NHP) 2017 that public spending on health would be increased from 1% to 2.5% of GDP by 2022, of which the Centre would spend 40%, that is, 1% of GDP. This year’s Economic Survey in fact makes a case for increasing the public health expenditure to 3% of GDP.

Ayushman Bharat Yojana

Let us finally discuss one of most ambitious, tom-tommed programs of the Centre, announced by PM Modi himself – Ayushman Bharat Yojana. It actually reveals the fundamental orientation of the Modi Government towards healthcare.

Ayushman Bharat Yojana has two components: Ayushman Bharat Health and Wellness Centres (HWCs), and Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (PMJAY)

The Health and Wellness Centres (HWC) scheme is aimed at improving rural infrastructure in health. However, this scheme is just a Modi ‘health jumla’. While it has been allocated Rs 1,650 crore in this year’s budget, and Rs 1,350 cr in last year’s BE and RE, these allocations are only a mere reshuffling of numbers; there is actually no real increase in government expenditure on rural infrastructure. This becomes obvious from the fact that the HWC scheme comes under the broad head National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) – the overarching mission of the Central Government to improve rural health services. And, the total allocation for NRHM has been falling in real terms over the last few years. The Ayushman Bharat Scheme was first announced by the Modi Government in the 2018 budget; the budget allocation for NRHM in this year’s budget is less than 2018-19 actuals, in real terms.

Incidentally, this same orientation can be seen in the attitude towards the urban counterpart of the NRHM, the National Urban Health Mission, whose objective is to address healthcare challenges in towns and cities with focus on urban poor. While the Union Cabinet had estimated the share of Central funding for this scheme to be around Rs 3,400 crore per annum way back in 2013 when it approved it,[11] allocation for this has remained much below this amount during the Modi years; in this year’s budget, it has been allocated a paltry Rs 1,000 crore.

Returning to the Ayushman Bharat Yojana, the other and most important component of it is the PMJAY. While announcing it, Jaitley proclaimed it as “the world’s largest government funded health care programme”. Under this scheme, the government promised to provide medical insurance cover of Rs 5 lakh per family to 10 crore poor families (roughly 50 crore people).

The impression given by this announcement is that it is a scheme to provide universal health care to the poor. But it is not so! It is only a hospitalisation insurance scheme. It does not cover outpatient costs, and these constitute 68% of the health related out-of-pocket expenditure (that is, personal spending by people) in India.[12]

Even as regards hospitalisation coverage, from the budgetary allocation under this scheme, it is clear that the government is not serious about this too. Thus, a 15th Finance Commission report estimated that total costs for PMJAY in 2019, taking then levels of hospitalisation rates and expenditure and assuming full coverage, would range between Rs 28,000 crore and Rs 74,000 crore, with projections for 2023 being more than double this range.[13] But actual allocation for this in this year’s budget is only Rs 6,400 crore. What is even more surprising is that despite the very large number of hospitalisation cases due to Covid last year, actual expense under this head as shown in the 2020-21 RE is only Rs 3200 cr (50% of the BE of Rs 6400 cr)!

There is another, and much more serious, problem with the PMJAY scheme. That has indirectly been admitted in this year’s Economic Survey. The Survey says that despite hospitalisation costs being much higher in private hospitals, “quality of treatment does not seem to be markedly better in the private sector when compared to the public sector.” (Economic Survey 2020-21, Vol 1, p. 163.)

If that is the conclusion of the government’s economic advisors, then why is the government pushing for an insurance scheme to treat the poor in private hospitals, instead of improving public hospitals so that people can be treated there at much cheaper rates?

The answer to this is the same as that we have given earlier in Parts 1 and 2 of this article, to explain other anti-people decisions of the Modi Government – the Modi Government’s meek acceptance of the conditionalities imposed on India by international finance capital, and implement neoliberalism.

The real agenda behind the Modi Government’s push to implement PMJAY is to privatise health care. As a part of this, the Centre has already announced incentives for the private sector to set up hospitals in Tier 2 and Tier 3 cities, to the extent of providing them grants (not a loan!) of up to 40% of the total cost of the project! As if this was not enough, the Niti Aayog and the health ministry have also recommended to all states that they partially privatise their district hospitals.[14]

But this would only increase out-of-pocket expenditure of patients, as most diseases do not require hospitalisation!

So, in name of “world’s largest healthcare initiative”, the Modi Government destroying whatever little that remains of India’s failing public healthcare system, and privatise it.

Notes

1. Calculated by us from data given in: Elementary Education in Urban India, Analytical Report, 2015–16 and Elementary Education in Rural India, Analytical Report, 2015–16, NUEPA, New Delhi.

2. See the statistics given in: School Education in India, 2015–16, Flash Statistics, U-DISE 2015–16, NUEPA, New Delhi, 2016, http://www.dise.in.

3. Tish Sanghera, “Fewer Children Out of School, But Basic Skills Stay Out of Reach: New Study”, 16 January 2019, https://www.bloombergquint.com.

4. India’s Missing Millions of Out of School Children: A Case of Reality Not Living Up to Estimation?‛ 2 November 2015, https://www.oxfamindia.org.

5. Calculations done by us, based on data given in: School Education in India, 2015–16, Flash Statistics, op. cit. We have taken the annual drop-out data for primary level, and used it to calculate the overall drop-out rate for primary education. Then, we have used the Transition Rate data and annual drop-out rate for upper primary level, to calculate the overall elementary level drop-out rate.

6. Ambarish Rai, “Budget Focus on Infrastructure, Digital Education Cannot Work in a Vacuum”, February 2, 2018, https://thewire.in.

7. J.B.G. Tilak, How Inclusive Is Higher Education in India? 2015, http://www.educationforallinindia.com; see also: Neoliberal Fascist Attack on Education, Lokayat publication, available on Lokayat website, http://lokayat.org.in.

8. Neoliberal Fascist Attack on Education, ibid., pp. 51-52.

9. “India’s Health Burden”, Down to Earth, https://www.downtoearth.org.in; “India Needs to Reform its Ailing Healthcare”, December 18, 2017, https://www.asianage.com; “R 3: Amount India Spends Every Day on Each Indian’s Health”, June 21, 2018, https://www.indiaspend.com; “Who Is Paying for India’s Healthcare?”, April 14, 2018, https://thewire.in.

10. Figures from Rural Health Statistics, 2017—18, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Govt of India: “RHS2018 – nrhm-mis.nic.in”, https://nrhm-mis.nic.in.

11. “Urban Health Mission to Cover 7.75 Crore People”, May 2, 2013, http://www.thehindu.com.

12. “Indians Sixth Biggest Private Spenders on Health Among Low-Middle Income Nations”, May 8, 2017, https://archive.indiaspend.com; “Evolution and Patterns of Global Health Financing 1995–2014”, April 19, 2017, https://www.thelancet.com.

13. Soham D. Bhaduri, “A health scheme sans clout”, March 10, 2020, https://www.thehindu.com.

14. “In the Wake of Ayushman Bharat Come Sops for Private Hospitals”, January 9, 2019, https://thewire.in; “Only a Strong Public Health Sector Can Ensure Fair Prices and Quality Care at Private Hospitals”, March 28, 2019, https://scroll.in; Shailender Kumar Hooda, “With Inadequate Health Infrastructure, Can Ayushman Bharat Really Work?”, November 26, 2018, https://thewire.in.