[Excerpted from an article in the Frontline issue of December 20, 1991, on Satyajit Ray, who went on to win an Oscar for lifetime achievement before his death in 1992.]

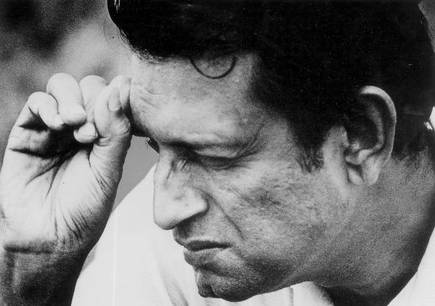

Satyajit Ray. Bengal’s contribution to cinema is every bit as important as Rabindranath Tagore. An awesome figure with worldwide reputation. A traditionalist in approach. A classicist in control. A humanist in attitude.

In an industry dictated by the box office, where “art cinema” shifts gears all the time, where radicals sneak into the middle-of-the-road, Ray’s untarnished aesthetics arouses admiration. Particularly now, when after suffering a heart attack, he works under constraints—aside from financial problems, he faces critical assessment which is not always flattering. This is underscored by the box-office bombing of Ganashatru (1989), the first-time television release of Shakha Proshakha (1990), and the response to Agantuk (1991), which wavers between the warm and the tepid. The avant-garde path-breaker has come to be seen as an established traditionalist.

Is Ray too slow to grasp today’s disillusionments and tomorrow’s impulsions? Has he become dated in treating his subject?

Buddhadeb Dasgupta shakes his head over Ray’s films since Ghare Baire (1984) as not having provoked comment as had films such as Pather Panchali and Charulata. “I don’t consider Ray a visionary. I don’t class him with [Akira] Kurosawa or [Ingmar] Bergman or [Kenji] Mizoguchi. Cinema for Ray is not the same as it was to them—somewhere between poetry and music. Why do I go back to a poem or a song that I have heard a thousand times? India hasn’t yet seen that kind of cinema.”

At this point it is useful to look at Ray’s description of his own life and work experiences in a rare public appearance in 1982. “For a film-maker, there is no readymade reality which he can straightway capture in a film. What surrounds him is only raw material. He must at all times use this material selectively. In other words, creating reality is part of the creative process, where the imagination is aided by the eye and the ear…. (In this process) the really effective language is both fresh and vivid at the same time, and the search for it is an inexhaustible one.”

Ray’s work reveals that this search for the effective, vivid and fresh language has remained as determined as it was when he began to pioneer a new trend way back in the 1950s. Mrinal Sen exclaims: “What a stupendous experience for Indian viewers, what a great revelation to the world audience! And it was Ray, an outsider, aided by an intrepid band of young dreamers, with practically no knowledge of the techniques of cinematography, who made an aggressive infiltration with Pather Panchali. With that, Indian cinema came of age.”

How did a bunch of newcomers create history with their very first film? Repetition does not dull the story. After some babes-in-the-wood adventures to locate a financier, Ray launched the film with loans from relatives and against his life insurance policy, and later by pawning wife Bijoya’s bangles. The story was Pather Panchali, a portion of Bibhuti Bhushan Banerji’s epic novel, long gestating in Ray’s mind. With him were art director Bansi Chandragupta and wizard lensman Subroto Mitra, who both shared the honours when they came.

It was one thing for young Ray to decide upon seeing Vittorio de Sica’s Bicycle Thieves that he was going to be a film-maker “working with non-professional actors, using modest resources, and shooting on actual locations exactly as de Sica had done”. But to develop the narrative techniques and stylistic elements—telling details, keen observation, and a suffused warmth of personal relationships—to realise the dream in an Indian setting required grit and tenacity besides inspiration. Stock responses had to be punctured, commercial stances spurned and conventional anaesthesia broken.

Iconoclastic as it seems, Ray’s work did have adequate preparation in the regional climate and his family background. Says Chidananda Dasgupta, “The attitude and content that Ray brought to cinema were both the direct outcome of what went on in the so-called 19th century Bengali Renaissance.” Ray belonged to be the Brahmo community—the first to relate westernisation to Indian tradition, which redefined Hinduism as a socially progressive national entity where the individual had the independence to interpret life through a system of values. “With this heritage from family and education at Tagore’s academy Santiniketan, he was all ready to break away from the traditional, historical and mythological moulds of Indian cinema,” says critic-writer Samik Bandopadhyay, adding the little-known fact of a precursor, Nemai Ghosh’s Chinnamol (1952), “which touched poverty and human suffering in the raw and without which Pather Panchali might not have been made the way it was”.

“For Ray the Italian neorealist cinema became the model because it grew out of the debris of the Second World War when Italian studios had been bombed out of existence. Shooting had to be in the open, in factory and hospital spaces, in the streets. It was impossible to recreate the Hollywood affluence in equipment or production. So we had a strange amalgam here in Calcutta,” chuckles Bandopadhyay, “of Hollywood techniques, Italian neorealism, early Russian revolutionary fervour (Eisenstein et al.) and the Bengali tradition, unlike anywhere else in the world.”

Diversity of interests characterises Ray’s Bengali Kayastha ancestors, with administrators, landowners, scholars (Persian and Sanskrit), academicians, a Tantric worshipper and a sportsman, “the father of Bengali cricket”, among them. Grandfather Upendrakishore Ray adopted Brahmoism, moved to Calcutta, started a press (U. Ray & Sons), ran a children’s magazine (Sandesh), and became famous as a pioneer in half-tone printing. He composed songs, played the violin and wrote and illustrated children’s books. Father Sukumar Ray was Bengal’s most renowned writer of Nonsense, whose mastery in the genre was acknowledged by Rabindranath Tagore.

Young “Manik”, as Satyajit was called, grew up amid creative effusions of various kinds—songs, verses, stories, illustrations, painting, graphics and also blockmaking and printing at the press located in his first home. Other influences came from an uncle who did photographic enlargement, a process which captivated Manik; he was later to indulge in photography himself. Another uncle intrigued him with his eccentricities and his dabbling with judo in midlife.

Growing up in his maternal uncle’s home after his father’s death, the shy and lonely Manik turned a voracious reader. His talent for drawing surfaced at school, while his love of Western classical music, especially Beethoven, began in childhood and became a passion during graduate studies at Presidency College. It was at Santiniketan, which he joined at the insistence of his mother, that Ray realised how deeply he yearned for Calcutta—“to mingle with the crowd on Chowringhee, to hunt for bargains in the teeming profusion of second-hand books on the pavements of College Street, to explore the grimy depths of Chor Bazaar for symphonies at throwaway prices, to relax in the coolness of a cinema and lose myself in the make-believe world of Hollywood”.

Advertising and graphics were to be Ray’s concerns for the next decade at the British-owned advertising agency of D.J. Keymer—as visualiser, illustrator, designer of book jackets and finally art director. Ray recalls that “Chowringhee was chock-a-block with GIs (American soldiers). The pavement bookstalls displayed wafer-thin editions of Life and Time, and the packed cinemas showed the very latest films from Hollywood.” He feasted on these films.

Apart from the sheer enjoyment of the visuals, Ray had been jotting down critical comments, star ratings, the hallmarks of great directors. He was devouring every film magazine and book in English and writing screenplays as a pastime. Besides the “never-growing” film club, Ray reconnoitred film journalism and made abortive attempts to turn scriptwriter.

Those were also the “adda” days of meetings at the India Coffee House on Chittaranjan Avenue, with writer Kamalkumar Majumdar and Satyajit Ray dominating discussions on every topic under the sun. At those stimulating sessions, Ray rigidly refrained from political or philosophic speculation.

How was it possible for a sensitive mind like Ray’s to have stayed aloof from direct participation in the tumultuous political and social upheavals in the country during young adulthood? How could he blanket them out of his vision of India, of the contemporary reality he wished to portray on the screen? These remain unanswered. The Bengal famine of 1943-44 was made into a memorable film by Ray later (Ashani Sanket–1973) but its trauma slipped by the graphic designer. Muses Chidananda Dasgupta: “His political sympathies have remained vaguely Left all his life in an idealised Fabian socialistic kind of stance. By staying away from politics he avoided exploitation, and those curbs arising from commitment to a political ideology.” Bandopadhyay refers to Ray’s oft-made statement that he would speak through his films and not words. But at times this silence has been broken. Ray refused to do a film of propaganda against the Chinese in 1962 when war broke out between India and China. It was to Indira Gandhi that he intimated his refusal to do a documentary on social welfare for the government. He led a huge, silent protest march against the killings during the food movement in West Bengal.

It is difficult to identify Ray’s target audience at first. Being neither commoditised nor entertainment-oriented, his films have failed to satisfy the masses. Ray has always been aware of the pressure to retain and renew this minority audience for his art films, particularly since they find no distributors as they did in the 1950s and the 1960s. Today, with some 36 productions—feature films, telefilms, documentaries (with acknowledged classics in the genre as those on Rabindranath Tagore and painter Binode Bihari Mukherji)—Ray has traversed a greater range of subjects than any other Indian film-maker. Ray has lived to see himself as a long-reigning monarch of Indian cinema. There are those like Prabodh Maitra (of Nandan, the West Bengal film centre) who believe the mantle of Tagore has fallen on Ray. A more conservative estimate accepts him as undoubtedly the best film-maker India has produced.

(Article courtesy: Frontline.)