The Christian community is celebrating Christmas, perhaps more joyously this season so as to get over the trauma and the gloom of the Covid pandemic. Most churches, however, did not have the traditional midnight mass, and parishioners of many city churches were requested to come early so that they could be allotted seats in churches observing a very strict social distancing. Many attended a virtual prayer service, live-streamed over the internet through dedicated portals or social media such as Facebook and YouTube.

As happens always in India, festivals are joyous not just for the community that may hold that day holy. Everyone else joins in, greeting friends professing that faith, but themselves also rejoicing in the “secular” aspects of the celebration. Everyone lights a candle on Diwali, and looks forward to special Eid dishes, especially the sweet vermicelli dishes. Ahead of Christimas, the queues at cake shops in cities such as Delhi and Kolkata are quite likely to have more Hindus and Sikhs than Christians.

And the ‘Christmas Tree’, a painting on a sheet of paper, or a branch lopped off the neighbour’s tree, decorated with tinsel and blobs of cotton wool, will be seen in many a home with young children. The power of television and internet, one could say.

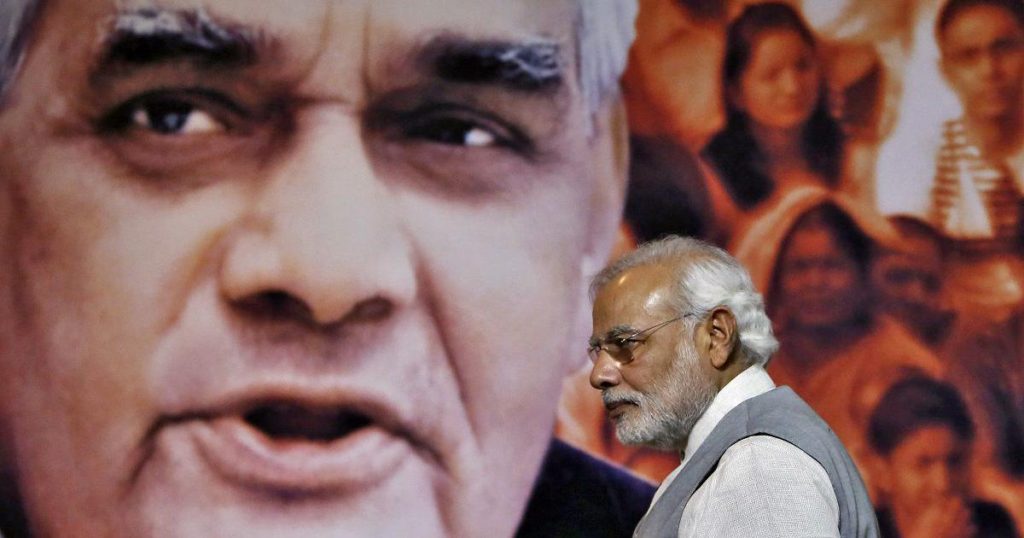

But for quite a few, it will not be a holiday of joy, but be observed as Good Governance Day where they may have to write an essay or take part in some other competition decided by the district authorities. That is how December 25 has been observed officially by the Indian government since Narendra Modi became prime minister in 2014 after winning the most polarising election in independent India. He said it was in honour of Atal Behari Vajpayee, the first prime minister from the Bharatiya Janata Party, who had been born on 25th December 1924.

Modi also announced a Bharat Ratna for his political senior who had been prime minister in three segments from 1998 till 2004, leading the National Democratic Front. Much to his surprise, the United Progressive alliance led by Congress president Sonia Gandhi cobbled a majority in the 2004 election. She chose economist and former finance minister Manmohan Singh to be prime minister, a position he held till 2014.

A surprise turn

Vajpayee, and political pundits, were surprised at this turn of events for the BJP stalwart was deemed to be a very a popular leader, within his party, and with the masses. He was affable, spoke Hindi as few politicians could, and dabbled in poetry of the sort that appealed to the young party men, full of patriotism and India’s cultural idiom. His avuncular figure stood in sharp contrast to his deputy prime minister, the dour Lal Krishan Advani. The two had guided the destinies of the BJP for much of the earlier three decades, even if lesser leaders held the titular position of party president.

Vajpayee was popular also with a large section of the religious minorities. He readily accepted requests of delegations to call on him. On his birthday, soon after going to church, large numbers of nuns, and the occasional archbishop or two, stood in queues to present him huge bouquets of flowers, and boxes of Christmas cake.

Ideologues of the Rashtriya Swayamsewak Sangh, which guided the BJP and of which Vajpayee was himself a lifelong member despite his unorthodox lifestyle, however told us back in 1997 that he was just a mask, the public relations or public face. At a meeting with three British diplomats, Govindacharya reportedly called Vajpayee the party’s mukhota (mask). “The real leader is party president L K Advani,’’ he was quoted to have said.

Vajpayee told journalists he was deeply hurt by the reported statement by a senior ideologue.

Vajpayee died in 2018, mourned by the nation, and hailed by world leaders. In his years in power, he had travelled to Pakistan by bus and made visible efforts to forge friendship with the neighbour with which India had fought four wars, one in his time as prime minister. He also detonated five nuclear devices in Pokhran, Rajasthan, in 1998, as much to remind the world that prime minister Indira Gandhi’s demonstration of Indian military nuclear technology was alive and kicking.

Pakistan followed suit with its own detonations. The nuclear rhetoric is not buried. Politicians revive it every election campaign.

In hindsight, for India’s religious minorities, both Muslims and Christians, despite his poetry, his food habits, and his human warmth, Vajpayee failed them at the crucial moments when they needed his assurance the most. Above all, when the chips were down, he sided with the hawks in his party, condoning the Sangh’s aggressive postures and actions. This was most obvious when the bigotry and aggression by Sangh affiliates turned violent, with arson, rapine, and mass murder.

Violence in the Dangs

Church leadership got a taste of it in his first year in office. Christmas eve of 1998 in Gujarat had seen focussed targeted violence against small rural churches in the tribal forested belt of the Dangs. Roving through the region that night, religious extremists torched every church of wooden pillars and tiled or thatched roof. Bigger buildings in the district capital Ahwa faced the terror of the mob.

A delegation of the church, led by Delhi Archbishop Alan de Lastic, who was then the president of the Catholic Bishops Conference and the United Christian Forum for Human Rights, spoke with the prime minister, requesting him to visit Dangs and see the arson for himself. Vajpayee took a helicopter ride to Ahwa, saw the damage with a grim face, and flew back to the national capital.

Asked by the media at his press conference on his return, Vajpayee suggested a “national debate on religious conversions.” He had, he said, also asked the government in Gujarat to take strict action against anyone trying to whip up communal tension. The government, he admitted, had failed to ban a Hindu rally on Christmas Day which led to the violence.

Mr Vajpayee said “he was aware that the Indian Constitution allowed everybody to propagate their religion”, but added that “maybe the time had come to take a fresh look at the subject”.

Archbishop Alan de Lastic reminded him that the matter had been discussed threadbare in the Constituent assembly. The Constitution was clear that people in India had the right to practice, profess and propagate their religion.

Alas, within weeks of Vajpayee’s press conference, one of the most gruesome acts of violence against Christians took place in Manoharpur in Orissa state where a Bajrang Dal activist, Dara Singh, led a mob which burnt alive an Australian, Graham Stuart Staines and his two young sons, Philip and Timothy, as the three slept in their jeep in a forest where they had come for a religious meeting of the tribals.

The incident shocked the world. The President of India called it a blot on the name of the country. Vajpayee sent a cabinet minister George Fernandes to Orissa. Fernandes came back and told the media there was a “foreign hand’ in the triple murder. Courts later sentenced Dara Singh to death, a sentence which the state high court commuted to a life term in prison. Staines’ widow, Gladys, said she had forgiven the killer, but the State was bound to take action.

Vajpayee’s insinuations of criminality in conversions to Christianity in India is the official dogma of the BJP, and more so of the RSS and its affiliates. The current spate of laws by several states against conversions are rooted as much in this as in the Islamophobia now rampant.

Islamophobia too took firm roots during Vajpayee’s time at the top. He was not unenthusiastic about Advani’s polarising Rath Yatra as the BJP flexed its muscles in its drive for political power, and the demolition of the Babri Mosque in 1992.

But it was in 2002 that Vajpayee, as prime minster for the third time, came short of the expectations of minorities. This time Narendra Modi, an RSS leader, had been catapulted as chief minister of Gujarat. The death of 59 Kar Sevaks in the burning train from Ayodhya triggered a massacre of Muslims in several districts of the state, including the capital city of Ahmedabad.

During a press conference in Ahmedabad on April 4, 2002, following the mass killings and rape of Muslims in central and north Gujarat, Vajpayee said he had advised chief minister Narendra Modi to observe ’Raj Dharma’, the duty of the ruler. Patently the advice was not heeded. There was bloodshed for three days at least, as mutilated and burnt bodies of the kar-sevaks were taken along a well-planned route, rousing the common people and cadres. The police seemed absent.

An early impression that the prime minister would ask the President to sack Modi as chief minister did not fructify. Political insiders later said Vajpayee had been told that by now Modi was more popular with the majority community than him, and a change in the state leadership would foment a rebellion.

The rest, as the cliché goes, is history.

(John Dayal is a veteran journalist and human rights activist. Article courtesy: Mainstream Weekly.)