Chicago, IL – I just returned from eight days in Luzon, the largest island in the Philippines, where the capital, Manila, is located. For many years, the movement for national democracy in the Philippines has asked for international solidarity, including human rights defenders to aid them in their struggle for economic and political rights. The presence of people from other countries can help diminish the violence of the Philippine military and national police against the movement. In addition, as national elections approach on May 9 there has been a rise in human rights abuses, and so the need for international solidarity is more pressing.

In 2016, Filipinos elected Rodrigo Duterte president. I was there just after his election. He campaigned promising to bring an end to the rule of the corrupt, wealthy elite that have run the country since independence from the U.S. occupation in 1946. Instead, he proceeded to intensify the repression against the movements of farmers, indigenous communities, workers, students and professionals who he claimed to champion. Hundreds of activists have been killed by the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) and the Philippine National Police (PNP), including priests and human rights lawyers.

War on drugs: War on the poor

Duterte also unleashed a “war on drugs” that was supposed to target the elites, including the four generals he identified in a campaign speech that he said were responsible for the flow of drugs coming into the country. In truth, it has been “a war on the poor,” as reported by INVESTIGATE PH of the International Coalition for Human Rights in the Philippines (ICHRP).

Six years later, over 30,000 drug users and small-time dealers – or people that the police claimed were users or dealers – have been murdered by the military or paramilitaries. The effect has been to create a climate of fear from a police and military occupation in the whole country, very much like that which Black and Latino communities have faced in U.S. cities for 50 years of our “war on drugs.”

Of course, the Philippines has suffered under American imperialist domination since the U.S. intervened against Spain in 1899. Like in Cuba and Puerto Rico, the Spanish were losing, and the U.S. saw an opportunity to become an imperialist power in the Pacific. The U.S. military waged a bloody war that lasted three years and resulted in the deaths of a million Filipinos. U.S. imperialism has never left the islands, despite granting independence in 1946.

The Philippines is a land rich in agricultural and mineral wealth, but because of their leaders selling them out to foreign investors, they have failed to develop their own economy. That’s why 6000 people leave the Philippines every day to work outside the country. The biggest landowners in the Philippines are U.S. corporations – Dole, for example.

The U.S. mass media – owned by the same corporate class that determines economic developments in the Philippines – reports on some of Duterte’s human rights abuses, including his attacks on opposition in the press. But they almost never report on the military carrying out massacres of trade unionists, peasants, or indigenous activists who dare to organize against the injustices facing the people.

Duterte: Time’s up

Because of the one-term limit in their 1986 constitution, Duterte’s presidency is coming to an end, but he is hoping his successors will be his daughter as vice president and Bong Bong Marcos, the son of the old dictator, as president. He needs them in office as an insurance policy.

As Tinay Palabay of Karapatan, the leading human rights watchdog in the country, explained to me, “Duterte loses immunity July 1. We are preparing cases for the International Criminal Court (ICC). Also in the UN, July will see three reports on human rights in the Philippines: by Michelle Bachelet, United Nations Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights (OHCHR); a Universal Periodic Review before the UN Human Rights Council; and an International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights treaty body review.” The three reports of the INVESTIGATE PH were submitted to the UN OHCHR and at the ICC.

Palabay also noted that beyond the national democratic movement, “The anti-Marcos vote won’t settle for a BBM (Bong Bong Marcos) victory in the Philippines.” In other words, if the Marcos/Duterte slate wins, there will be a great increase in resistance to the new regime.

Electoral struggle/mass struggle: Basic demands for human rights and peace in the Philippines

Running against the Marcos/Duterte slate is Leni Robredo, the current vice president, and Senator Francis “Kiko” Pangilinan. Leni and Kiko are also supported by 1Sambayan, a broad coalition of democratic forces banded together to pursue a common cause. Running on the senatorial slate of 1Sambayan are leading activists from the mass movements, including Congressman Neri Colmenares, who was detained and tortured under the martial law regime of dictator Ferdinand Marcos (1972 – 1986); and Elmer “Ka Bong” Labog, president of the Kilusang Mayo Uno (KMU), the most important Labor Center in the country. Kilusang Mayo Uno means May First Movement.

I was able to talk with Amirah Lidasan, a Muslim woman activist from the Moro nationality on the island of Mindanao, running for congress as a third nominee of Bayan Muna (People First) Partylist. It is one of the partylists under MAKABAYAN Bloc (Patriotic Bloc) with different member partylists including Anakpawis, which translates to “toiling masses.”

For more than 50 years, the massive national democratic movement has led heroic efforts by the Filipinos to free themselves from U.S. domination, from foreign corporations cruelly oppressing them, and to demand genuine agrarian reform – “land to the tiller” as Antonio Flores expressed it. Flores is popularly known as Ka Tonying (Comrade Tonying). He is chair of Unyon ng mga Manggagawa sa Agrikultura (UMA), the farm workers union. It is well known that 70% of farmers in the Philippines are landless. While employment statistics suggest that the Philippines is no longer a farm economy, but a service economy, Ka Tonying said, “Farmers don’t see it that way.”

Red-tagging

Under Duterte, the AFP and PNP are carrying out more and more brazen attacks on organizers. Their targets include the KMU. In March 2021, they killed nine trade unionists in what has been called Bloody Sunday.

They have also targeted the officers of the KMU. Last week, I went to meet with KMU National Capital Region Secretary General Ed Cubelo. In March 2020, Ed was “red-tagged.” Red-tagging is what it sounds like. When authorities or anonymous actors put up vinyl banners (called tarpaulins or tarps), use spray paint, or a small picket line to accuse an activist, an elected official, or anyone of being a communist or a soldier of the New People’s Army (NPA). The purpose of red-tagging, or “terror-tagging” is to intimidate those with the courage to speak out.

In October 2021, Facebook accounts were created accusing him of membership in the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) and the NPA. Then on December 13, 2021, he received death threats.

Last month, the PNP escalated. The barangay (neighborhood organization with elected officers who have roles to administer schools, fire, police, parks) held a job fair on the street in front of his house in Metro Manila. Two PNP officers entered his house without permission. As a result, brother Cubelo is no longer living at home.

On February 23, another massacre was carried out near the city of Davao on the island of Mindanao, where I visited in 2016. Known as the New Bataan Five, two teachers, a health worker, and two drivers were murdered. Most were part of the Lumad, the indigenous people of the southern Philippines.

In both this case and that of Bloody Sunday, people in the area said there was no encounter between two armed groups. These were just two more of the long string of murders carried out by a military funded and backed by the Pentagon.

Given the murders of hundreds of activists, in addition to 30,000 of the urban poor in the past six years, there is good cause for Filipino activists to be very concerned when they get red-tagged or terror-tagged. The real source of terror in the Philippines is of course Malacañang Palace, the residence of the president.

I get red-tagged

Sunday morning, April 10, at 1 a.m., men identifying themselves as CIDG (Criminal Investigation and Detection Group) hung banners in front of the hotel where I was staying in Quezon City, part of Metro Manila.

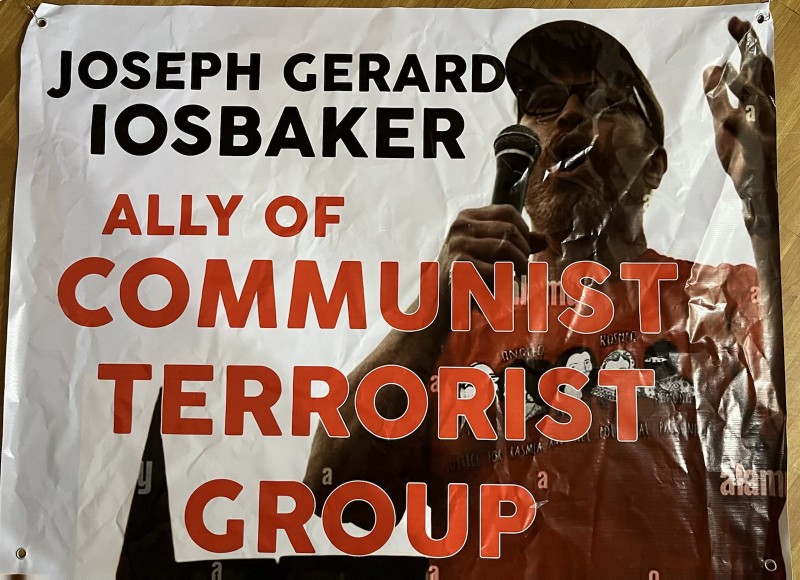

The four feet by five feet vinyl banners had a full color Getty Images photo of me when I spoke at the mass rally in Manila in July 2016. Held on the occasion of President Duterte’s first State Of the Nation Address (SONA), the People’s SONA is an annual affair. I spoke as a representative of the largest international solidarity delegation – over 300 people – who were there among the 30,000 in the rally.

The banners accused me of interfering in the affairs of the Philippines and called me a “Communist Terrorist Ally.” There were more of the same banners hung at a nearby human rights office housed in the National Council of Churches building.

The next day, a missionary worker woke to find banners with the same messages and her face hanging in front of her home. She had been with me in some meetings during my eight-day visit.

The mission of CIDG is to combat organized crime groups. It’s probably not a coincidence that their offices are near where I was staying and are housed in the same building as the NTF ELCAC, Duterte’s National Task Force to End Local Communist Armed Conflict. This body was created by Duterte to systematize red-tagging and link up police investigation work to stop protest movements more effectively.

Solidarity is not a crime

Of course, the missionary and I don’t face the prospects of being killed or tortured. I remember in 2010 when FBI agents raided my home and six other homes and an office of anti-war and international solidarity activists. They alleged the Midwest Antiwar 23 had information about or were providing material support to “foreign terrorist organizations” in Palestine and Colombia. Justice Department prosecutors also brought up the Communist Party of the Philippines and the New People’s Army. The U.S. put them arbitrarily on the State Department list of foreign terrorist organizations after 9/11.

We were subpoenaed to appear before a kangaroo court called a federal grand jury. Each of us said then that we would never talk to the FBI or the grand jury. From files left behind in one of the raided houses, we know that the FBI and the grand jury wanted us to tell them who we knew in Palestine and Colombia. In those countries, like in the Philippines, anyone we named would face torture or death, not just prison time.

The Antiwar 23 all took the position we would rather face prison time than contribute to the torture or murder of a freedom fighter.

We said then that solidarity is not a crime. And today again, that must continue to be our stand.

Finally, U.S. imperialism, not us, is who is interfering in the Philippines.

Long Live International Solidarity!

(Courtesy: Fight Back!, a publication by activists and organizers of various trade unions, low-income community, and other people’s movements in the USA.)