Prabodhan Pol

In India, despite the presence of peculiar social institutions like caste, the role of the newspapers in social reforms movement was not just limited to articulation of specific concerns of individual reformers. But they also laid the foundations of a mass churning that aspired for democratic values.

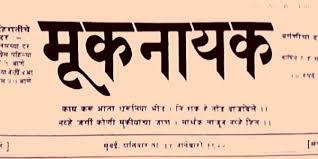

On January 31, 1920, one hundred years ago, one such newspaper Mooknayak was founded by B.R. Ambedkar. Mooknayak literally translates as the leader of the voiceless.

Mooknayak’s establishment in 1920 reflected the conspicuous shift in the socio-political discourse on caste and untouchability in India. Despite its short life, Mooknayak laid the foundations for an assertive and organised Dalit politics. It announced the arrival of a newer generation of anti-caste politics that broke the confines of region, language and political boundaries and coincided with larger developments on the national scene.

Mooknayak also faced several major challenges which include issues of finances and management. The lessons from the Mooknayak experiment not only helped Ambedkar in bringing out his later newspapers. The articles carried in it were an instructive exercise for many forthcoming generations of Ambedkarite activists.

Beginnings

Mooknayak was published from Bombay on alternate Saturdays. The title of the newspaper was probably inspired by the quatrain written by Marathi Bhakti poet, Tukaram. This particular quatrain also found place beneath the heading of the paper.

Why should I feel shy?

I have laid aside hesitation and opened my mouth.

Here, on earth, no notice is taken of a dumb creature;

No real good can be secured by over-modesty.

Interestingly, Ambedkar was never officially associated with the operations of Mooknayak. He worked as its ‘behind the scene’ de facto editor for at least six months, before leaving India to continue with his doctoral studies at the London School of Economics.

He is believed to have edited 12 issues in the span of six months. The first official editor of the Mooknayak was Pandhurang Nandram Bhatkar. Bhatkar, an employee of the Bombay Port Trust, was one of the known activists working in the Bombay based Dalit–non Brahmin activist circles.

Before his stint as an editor, Bhatkar, a graduate from Fergusson College, Pune, came into limelight due his marriage to a Brahmin woman in Bombay. He, however, held a largely ceremonial position at the paper. In July 1920, he was replaced by Dnyandev Gholap, who also had experience of working for Mooknayak as its manager and accountant.

Gholap had assisted Ambedkar in 1919 in preparing a memorandum of demands to be submitted to the colonial government. He attained a unique reputation of becoming the first nominated member from the untouchable community to find place in the Bombay Legislative Council.

Gholap played a vital role as the editor of Mooknayak. But due to complaints of mismanagement of the periodical, ties between Gholap and Ambedkar got bitter in later years. Subsequently, from 1923 onwards, Ambedkar distanced himself from the activities of Mooknayak. Soon after, following a public spat with Ambedkar, Gholap left Bombay for his native village in Satara. He then restarted Mooknayak here, with a new title, Abhinav Mooknayak. This periodical didn’t have a long life, mostly due to lack of finances and subscriptions. Gholap later joined the Congress.

Meanwhile, Ambedkar received Rs 2,500 for Mooknayak from Shahu Maharaja of Kolhapur. The money was instrumental in the initial establishment of the periodical.

The price of a single copy of the Mooknayak was 2.5 ānā, and the annual subscription was Rs 2.50. The circulation of the newspaper was limited to 700 subscribers in July 1920; by July 1922, the circulation had risen to 1,000 subscribers.

But the paper faced serious financial and management problems since its inception. In the times of financial crisis, Ambedkar’s close Parsi friend Naval Bhathena provided vital funds. Bhathena, an entrepreneur himself, was a classmate of Ambedkar at Columbia University.

The friendship between Ambedkar and Bhathena was particularly interesting as despite being a Gandhi admirer and Congress supporter, Bhathena and Ambedkar remained lifelong friends. In Ambedkar’s absence, it was Bhathena who financially bailed out Mooknayak on several occasions. He also helped Mooknayak reach out to big businessmen like Godrej for ads.

Being a periodical run by the members of the untouchable community, it faced systematic prejudice that affected its regular operations. For example, in an article in the Bahishkrut Bharat, another newspaper started by Ambedkar, there is a mention of the refusal of the nationalist newspaper, Kesari (founded and edited by Bal Gangadhar Tilak) to publish a simple announcement regarding the inauguration of the first issue of Mooknayak. There was an established convention, prevalent amongst papers of those days, to publish such an announcement of fellow publications on the eve of their establishment. Kesari not only rejected the proposal to publish such an announcement free of cost, it refused to print it even after payment was offered.

Later, nationalist newspapers like Kesari and Bombay Chronicle became the vocal opponents of Ambedkar and his politics.

Mooknayak and organised Dalit politics

Mooknayak carried reports and opinions particularly dealing with western India.

But we also find insightful responses to pan-India concerns. One of the important components of Ambedkar’s newspapers (including Mooknayak) was the regular publication of letters sent by common Dalits, demanding immediate attention to their particular cases of caste oppression and violence.

The power of these letters stands as testament to the strength newspapers had attained in colonial times. Through these letters, Mooknayak not only helped to vocalise the everyday concerns of the untouchable communities but also argued for the necessity of organised mass-based Dalit politics.

It is therefore not a coincidence that in 1924, Ambedkar founded Bahishkrut Hitkarni Sabha, an organisation oriented towards mass mobilisation, with the motto ‘educate–agitate–organise’.

Mooknayak highlighted the limitations of the then non-Brahmin perspective to understand the Hindu society through the binary of Brahmin and non-Brahmin categories. It argued that though the binary had a substantial political value, it nonetheless glossed over the internal contradictions within the non-Brahmin community.

The debates and discussion in the paper also help us to understand the complicated nature of caste society and the fact that it can’t be defined with a simple narrative.

Most importantly, with the establishment of periodicals like Mooknayak, the caste-ridden nature of the political discourse of those days became conspicuous. For example, Ambedkar’s critique of Indian nationalism was not directed against the politics of anti-imperialism as was portrayed by his opponents. It simply argued that Indian nationalism arrogantly invisibilised the caste question. Nationalism as a political ideology, therefore, would have a very limited significance to the marginalised communities.

Ambedkar argued in Mooknayak that the development of nationalist consciousness was not solely contingent on conventional attributes such as common religion, culture and past, but through inclusiveness and equal participation in the deliberations of society.

It was in the pages of the Mooknayak that Ambedkar famously compared Indian society with the metaphor of a dysfunctional multi-storeyed tower. Each floor had no stairway to connect with the other. Here, the tower represented caste stricken ‘suffocated’ society and each floor in the tower constituted an individual caste. Mooknayak here made an important point that a collective consciousness that forecloses opportunities of social interaction would not develop into a strong united society at any point of time.

Therefore, any politics of collective identity, only focusing on the glorification of culture, tradition and the past, without acknowledging detrimental social traditions, might not work to make any country a nation. Therefore, the rhetoric of nationalism, according to Mooknayak, would not work in the long-term, unless social–religious discriminations and the institution of caste were completely annihilated.

These are concepts which resonate particularly today.

The advent of the Mooknayak was symptomatic of the rise of Dalits in the public sphere. Printed pamphlets, leaflets and periodicals became easiest vehicles to generate public activism amongst the masses.

Bombay, being an industrial centre and a hub of untouchable migrant population, became the nucleus of organised Dalit activism. The requisite intellectual and material resources were possible only due to Bombay’s vibrant Dalit migrant population. Although Mooknayak struggled to survive, it nevertheless helped in the institutionalisation of print culture among Dalits in western India.

Prior to the Mooknayak, the criticism of Hinduism remained an exclusive domain of non-Brahmins, with very few from the Dalit community joining in the critique. With the emergence of the Mooknayak, the process of politicisation of the Dalit question had begun. It paved the way for pan-Indian Dalit politics.

The hundredth anniversary of Mooknayak also highlights the predicament of the present times. Despite a strong presence of Dalit–Bahujan voice in the political domain for past many decades, mainstream media has failed to provide significant space for Dalit–Bahujans in it.

Dalit journalists still have to struggle to find their places as employees in prominent media organisations. It therefore becomes pertinent for everyone to revisit the content and context of Indian journalism from the lenses of caste.

(Prabodhan Pol currently teaches history at Manipal Centre for Humanities (MAHE), Manipal, Karnataka.)