Budget 2022-23: What Is in it for the Poor?

Part V: Proposal for an Alternate, People-Centric Budget

1. Why are Indian Government’s Social Sector Expenditures So Low?

As we have discussed in Part III of this budget series, the Indian government’s social sector expenditures are not only way below those of developed countries, in the words of a recent RBI report, they are also “woefully below peers”—like South Korea, Latvia, Poland, Slovak Republic, Czech Republic and so many other countries mentioned in this RBI report (See Chart 4, which is reproduced from the RBI Bulletin).[1] This RBI report of 2018 based itself on data for 2014–16. Since then, the Modi Government has made further cuts in its already low welfare expenditures. This includes cuts in the most important schemes aimed at providing the most essential services to people, like food and rural employment.

Chart 4: Social Sector Expenditures of India and Peer Countries, from RBI Bulletin

Even after the pandemic struck the country in early 2021 and the economy collapsed due to the lockdown, pushing crores of people to the edge of starvation, the government refused to increase its social sector expenditures by a significant amount. The relief package announced by Prime Minister Modi himself of Rs 20 lakh crore, equivalent to almost 10 percent of the GDP, turned out to be sheer bombastry of the highest order. The bulk of the financial assistance promised by the government was in the form of loan offers; the actual expenditure made by the government from its budget, which alone can be called a ‘relief package’, was just around Rs 2 lakh crore, or one-tenth of the amount announced by the PM, a ridiculous sum as compared to the scale of the massive economic devastation being faced by the people. It was the lowest relief package amongst all the major economies of the world.[2]

Why is the government not willing to increase its social sector expenditures—and that too when the country is facing an ‘unemployment, poverty and hunger emergency’? The government claims that it does not have the money, that it is facing fiscal constraints; the finance minister has often claimed that the government’s subsidy bill is becoming “unmanageably high”; mainstream economists also claim that the government is financially constrained and should rationalise its subsidy bill—a euphemism for saying it needs to be reduced; intellectuals writing in the media express delight whenever the government cuts its social sector expenditures.

All of them are lying! That our government cannot significantly raise its social sector expenditures is humbug!

The government claims that India is one of the world’s fastest growing economies, and that we are on the way to joining the ranks of the developed countries. Even if there is some exaggeration in these claims, the government can at least raise its social sector expenditures to the level of countries at a similar level of development.

While the poverty levels in our country are appalling, among the worst in the world, it does not mean our country is poor—we have the third largest number of (Forbes) billionaires in the world, after the USA and China (figure for 2021). The reason for our huge poverty levels is that our country is among the most unequal countries in the world. And this inequality has been increasing over the years—which means that the rich are cornering most of the wealth being generated in the country. The Gini co-efficient, which measures income inequality in various countries, for India has increased from 74.7% in 2000 to 82.3% in 2020 (a higher index indicates greater inequity).[3]

The real reason why the Modi Government doesn’t want to increase its social sector expenditures is related to this extreme inequality: it has been doling out enormous amounts of subsidies to the big corporate houses and the rich. These subsidies are to the tune of several lakh crore rupees every year! Because of this:

- The total government revenues themselves are very low; we have given figures for this in Part I of this budget series, showing that the total revenues of the Government of India (Centre+States combined) are much below the global average;

- Even with regards to the limited government revenues, the Modi Government’s priority is to transfer them to the coffers of the rich.

Obviously then, the Centre is not going to have money to spend on social welfare schemes.

In a deft use of language, while the breathtaking ‘subsidies’ given to the rich are euphemistically called ‘incentives’ and justified as being necessary for ‘growth’, the social sector expenditures—whose purpose is to provide the bare means of sustenance to the poor at affordable rates—are condemned as ‘subsidies’, as being wasteful, inefficient, benefiting the middle classes rather than the poor, promoting parasitism, and so on.

Here is a snapshot of some of the subsidies being given to the rich:

a) Tax Exemptions and Cuts

The Modi government has sharply reduced the corporate tax rates. In September 2019, the FM sharply reduced the base corporate tax rate to 22% from 30% (including cess and surcharge, effective tax rate 25.6%) and to 15% from 25% for new manufacturing companies (including cess and surcharge, effective tax rate 17.01%). While making the announcement, the FM also admitted that this would lead to a loss in direct tax income of nearly Rs 1.5 lakh crore every year. This got reflected in a sharp fall in corporation tax receipts in the 2020–21 budget—the RE shows a revenue of Rs 6.11 lakh crore, as against a budgeted Rs 7.66 lakh crore.

This tax cut did not benefit the smaller companies, who in any case were paying lower taxes. The Economic Survey 2019–20 admits that this tax cut benefited the largest 4,700 companies with gross turnover of Rs 400 crore—and these companies constituted just 0.9% of all the companies in India. [4] These companies are so big, and already dominate the Indian market, that this tax cut will not incentivise them to make more investments—all it will do is increase their profits. Thus, the net effect of this tax cut is, that government revenue has come down while corporate profits have gone up. Or, may we say that it is a roundabout way of transferring public money to private coffers!

The steep cut in corporate taxes has made India among the countries with the lowest corporate tax rates in the world. France has a corporate tax of 31% to 33.33%; Germany also a similar net corporate tax rate; total corporate taxes in the USA and Canada are around 30%, while in Brazil this is at 34%. Even our neighbour Bangladesh has a 35% corporate tax[5]—and several recent newsreports point out that the Bangladesh economy is definitely doing much better than India on several counts, most importantly in its human development indicators.[6]

The personal income tax on high incomes has also come down sharply in India over the years. Other types of direct taxes, such as wealth tax and property tax, on the rich are also very low, as compared to the developed countries. Wealth tax was in fact abolished by the previous FM Arun Jaitley of the Modi Government in 2015. This is despite the fact that wealth and income inequalities in India have been increasing over the years. According to the latest World Inequality Report 2022, in India, the share of the bottom 50% in income is just 13%; while the share of the top 10% is 57% and the share of the top 1% is as high as 22%. Shamefully, this income inequality is even more extreme than during the colonial period—when the income share of the top 10% was around 50%. [7] Yet, due to low income tax rates, various kinds of exemptions, deliberate loopholes in tax laws, etc., the rich are having a gala time. The overwhelming majority of the ultra-rich in the country pay hardly any taxes. Data made available by the Income Tax department reveals that in 2017–18, just 20 individuals paid a tax of more than Rs 50 crore.[8] This, despite the fact that in 2018, according to the Forbes list of world’s billionaires, India had 141 dollar billionaires!

Consequently, India’s personal income tax collection both as a percentage of revenues and as a percentage of GDP is much lower than not just the USA and OECD but also the BRICS countries (as a percentage of GDP, personal income tax in USA was 10%, around 8% for the OECD countries, 5% for China, 3.6% for Russia, and 8.5% for South Africa, but was just around 1% for India.)[9]

Apart from lowering the tax rates, during the past eight years it has been in power, the Modi Government has also been giving various tax exemptions to the rich—in corporate taxes, income taxes and excise duties—of several lakh crore rupees every year. An analysis of the Union Budget documents reveals that these exemptions total at least Rs 44 lakh crore over the period 2014–22 (while making these calculations, we have excluded the revenue foregone due to concessions given on personal income tax, since this write-off benefits a wider group of people).[10]

b) Loan Waivers

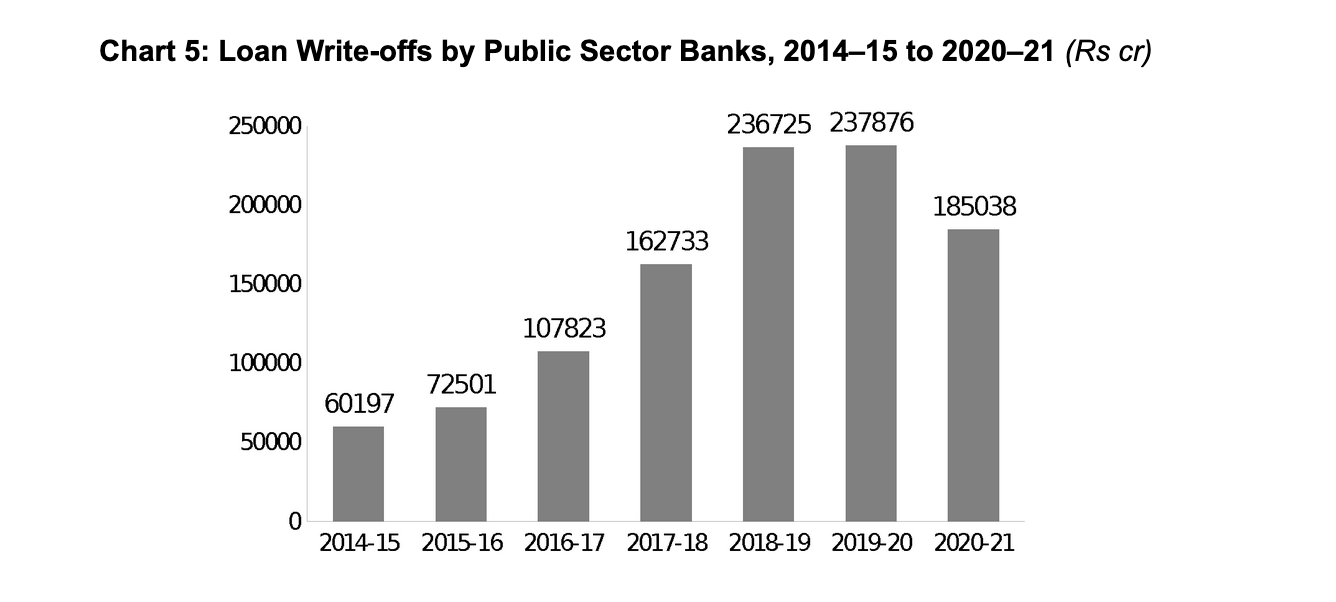

During the first seven years of the Modi Government (that is, 2014–15 to 2020–21), public sector banks have waived loans of at least Rs 10.63 lakh crore (see Chart 5).[11]

This figure does not include the interest accruing on these loans; including that, the loss would be four times this amount.[12]

Additionally, public sector banks have restructured loans of the ‘high and mighty’—a roundabout way of writing off loans—probably of the order of several lakh crore rupees (the actual amount is not known).[13]

Even after all these write-offs, the total non-performing assets (a euphemism for bad loans) of public sector banks had gone up to Rs 8.35 lakh crore as of March 2021.[14] Considering the nature of the ruling regime, the great majority of these are also going to be written off very soon.

The overwhelming majority of these loan waivers / restructurings / NPAs are big loans to corporate houses.[15]

Adding up all these amounts, it means that since it came to power in 2014, the Modi Government has written off, or is in the process of writing off, around Rs 30 lakh crore of loans to big corporate houses. (This estimate assumes that write-offs in the name of loan restructuring are as much as the loan write-offs. This figure does not include interest accruing on these loans; including that, the figure may be much more than this.)

c) Other Transfers of Public Funds to Private Coffers

The Modi Government has been handing over control of the country’s mineral wealth and resources to private corporations in return for negligible royalty payments, transferred ownership of profitable public sector corporations to foreign and Indian private business houses at throwaway prices, given direct subsidies to private corporations in the name of ‘public–private–partnership’ for infrastructural projects, and so on. These transfers of public wealth to private coffers have resulted in enormous losses to the public exchequer. We have discussed some of these transfers in Part I of this budget series.

It is difficult to put a figure to the loss being incurred by the exchequer on account of these transfers of public wealth to corporate houses, as much of these losses are notional. But they should be in the range of several lakh crore rupees per year.

d) Refusal to Act against Black Money

One of the important promises made by the Narendra Modi during the 2014 elections was that if voted to power, he would take action to bring back the black money stashed abroad by the corrupt, and deposit Rs 15 lakh in the account of every citizen.

But after winning the elections, the Prime Minister Modi made a complete U-turn on the issue. In fact, soon after coming to power, the Modi Government went to the extent of refusing to divulge the names of foreign account holders in the Supreme Court. Commenting on the application moved by the attorney general on behalf of the government in the Supreme Court, senior advocate Ram Jethmalani, who was the petitioner in the case, stated, “The government has made an application which should have been filed by the criminals. I am amazed.”[16]

This is despite the fact that there have been several leaks of names of Indians who have stashed away black money in illegal bank accounts in tax havens abroad. This includes the ‘Swiss Leaks’ of February 2015, when names of 1,195 Indians with accounts in HSBC’s Geneva branch were released by the Indian Express; and the ‘Panama Papers scandal’ of 2016 wherein names of 500 Indians with links to offshore firms were made public. These names include prominent Indian businessmen, diamond traders, politicians, and film stars. Most recently, in October 2021, the Indian Express reported yet another leak of offshore financial records of several hundred wealthy individuals and businesses in what has come to be known as the ‘Pandora Papers’. This list contains the names of more than 300 Indians. [17]

The Modi Government has so far not prosecuted any of these individuals. Instead, it has been diluting the anti-corruption legislations in the country.[18]

Not only that, it has modified the laws to make corporate funding of political parties opaque. The Telegraph quotes a senior officer with the CAG as saying, “… this throws open the possibility that an order to build a highway or a railway bridge could be given to a firm and that firm could pay the donation to the party in power which placed the order with it.”[19] But such is the power of the BJP propaganda machine that people still believe that the BJP is serious about tackling corruption.

e) Consequence: Low Government Revenues

In every capitalist country in the world, including the developed capitalist countries, while their governments essentially run the economy for the profiteering of the rich, they also collect significant amount of taxes from them and spend it on providing education, healthcare and other welfare services for their people.

In contrast, in India, the tax and non-tax concessions and transfers to the corporate houses have reached such mindboggling levels under the Modi Government that India’s total government revenue as percentage of GDP is not only far below the developed countries, it is also way below the other Emerging Market Economies (see Part I of this budget series for figures).

Even if the government reduces some of these concessions / transfers to the corporate houses and thereby increases its revenues from the present 19.3% of GDP to the level of other Emerging Market Economies, that is, to around 28% of GDP, it would mean an increase in its revenues by a massive 8.7 x 2,58,00,000 /100 = Rs 22,44,600 crore or Rs 22.45 lakh crore. Our total budget outlay (for 2022–23) would go up from Rs 39.45 lakh crore to Rs 61.9 lakh crore! That is more than enough to finance a huge increase in our social sector expenditures and bring them to near the levels of other Emerging Market economies. Let us see how this can be done.

2. An Alternate, Pro-People Budget: Some Suggestions

If the government partially withdraws some of the concessions / subsidies / transfers of public wealth being given to the rich, and imposes some additional taxes on them, it can raise enough additional revenues to finance a big hike in its social sector expenditures. Here are a few examples of the measures the government can take.

i) Reducing the Huge Tax Concessions Given to the Rich

The Modi Government has been giving at least Rs 6 lakh crore in tax concessions to the rich every year. Even if the government reduces these concessions by 75 percent, it will result in an increase in the government’s annual tax revenues by Rs 4.5 lakh crore. (This figure excludes the possible increase in revenues if the government takes action to curb illicit flows of money.)

ii) Reducing the Huge Transfers of Public Funds to the Rich

The government is transferring huge sums of public money – of the order of several lakh crore of rupees – to big business houses. Just the loan waivers total around Rs 2+ lakh crore every year. Even if it partially withdraws these concessions, it will increase government revenues by several lakh crore rupees every year. For our calculations, let us conservatively assume this increase to be Rs 3 lakh crore every year.

iii) Imposition of Wealth Tax on the Richest 1 percent

There is nothing very anomalous about a wealth tax. In fact, inequality in the world has grown to such extremes that even the annual jamboree of the world’s super rich held at Davos, Switzerland has expressed concern, and ‘establishment’ economists across the world have been demanding imposition of wealth taxes on the rich to reduce it. Wealth taxes exist in several European countries. [20]

According to an estimate made by Credit Suisse in 2021, the total wealth of the country in 2020 was $12833 bn, of which the richest one percent in India owned 40.5 percent. This works out to $5197.4 billion or Rs 384.61 lakh crore.[21] The wealth of India’s richest has boomed even during the pandemic, the government’s income taxes also saw a 26% increase (2021–22 RE over 2020–21 A). This year, the Centre has made a conservative estimate of increase in income tax revenue, by 14%. So if we conservatively assume that the total incomes of the rich increase by 15% per year, their wealth in 2022 would be Rs 508.13 lakh crore.

Imposition of a low 2 percent wealth tax on this would earn the government Rs 10.16 lakh crore in revenue. (Incidentally, during the 2020 USA Presidential elections, both Warren and Sanders had proposed a minimum wealth tax of 2 percent, rising to 6 / 8 percent for those with fortunes over $1 billion).

Additionally, the government can also impose a wealth tax of 5% on the country’s billionaires. There were a total of 142 billionaires with a total wealth of $719 billion in 2021. Assuming an increase of 15% in their wealth for 2021–22, their wealth would go up to $827 bn or 61.19 lakh crore. An additional 3% tax on their wealth would yield a revenue of 1.84 lakh crore.

Thus, the total increase in government revenues by imposition of this modest wealth tax on the country’s richest 1% people would lead to an increase in the government revenues by Rs 12 lakh crore.

iv) Imposition of Inheritance Tax on the Richest 1 percent

This tax is also perfectly in sync with the ideology of capitalism. While supporters of capitalism argue that the rich are so because of their special qualities like ‘innovativeness’ and ‘entrepreneurship’, there is no reason why their children should be in possession of all their wealth; and so it is perfectly justified if governments impose a substantial inheritance tax on the very rich. Several developed countries had a large inheritance tax till the 1980s; during the past three decades, due to the rise of neoliberalism, many have either removed or reduced it. Recently, an OECD report called for (re-)introduction of inheritance tax as a way of reducing wealth inequality. Inheritance tax rate in France continues to be 45 percent, and in South Korea and Japan is 50 percent.[22]

For India, if the government imposes a modest inheritance tax rate of 33 percent on the richest 1 percent people in the country, then, assuming that about 5 per cent of the wealth of these top 1 per cent gets bequeathed every year to their children or other legatees, the government would earn 508.13 lakh crore x .05 x .33 = Rs 8.38 lakh crore as inheritance tax revenue every year.

v) Total

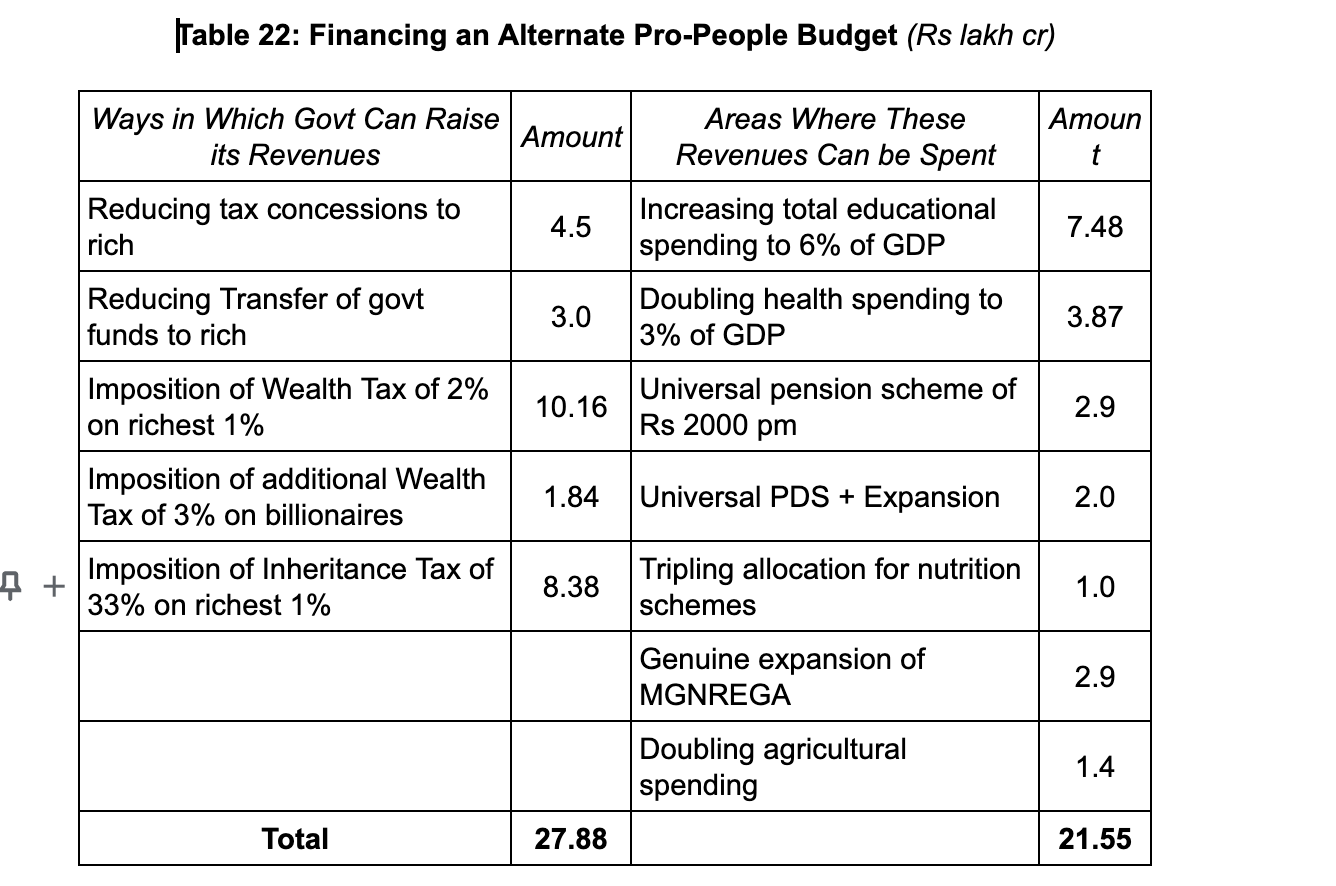

These four suggestions given above would fetch the government an additional (4.5 + 3 + 12 + 8.38 =) Rs 27.88 lakh crore in revenue. That would send our budgetary outlay zooming from Rs 39.45 lakh crore in 2022–23 BE to Rs 67.33 lakh crore (See Table 22).

Financing a Huge Increase in Social Sector Expenditures is Dooable

Assuming that the government’s social sector expenditures (Centre + States combined) in 2022–23 are 8.6% of GDP, as per the Economic Survey of 2021–22. Assuming that this year’s social sector expenditures remain the same, that would amount to Rs 22.19 lakh crore. This means that if the Centre reduces some of the enormous subsidies it is giving to the rich and implements the suggestions given above, the resulting increase in Centre’s revenues of Rs 27.88 lakh crore would be enough to more than double the total social sector expenditures of both the Centre and States combined.

To be more specific, this increase in government revenues would be more than enough to finance:

i) An increase in total educational spending (Centre + States) to 6% of GDP, from the present 3.1% of GDP. Additional spending required = Rs 7.48 lakh crore.

ii) An increase in total health spending (Centre + States) to 3% of GDP, from the present 1.5% of GDP. Additional spending required = Rs 3.87 lakh crore.

iii) Implement a universal pension scheme and provide all the old people in the country a (non-contributory) monthly pension of Rs 2,000 per month. There are an estimated 12 crore people in the country above the age of 60. So cost to government = 12 crore x 2000 x12 = Rs 2.9 lakh crore.

iv) Implement a universal PDS, and provide all citizens 35 kg of rice /wheat and 5 kg of millets (at Rs 3/2/1 per kg respectively) and 2 kg of pulses and 1 kg of edible oil (at subsidy of Rs 50 per kg for both) per household per month. Additional spending required = Rs 2 lakh crore (for 2021–22).[23]

v) Triple government expenditure on nutrition schemes (including anganwadi services, Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana and Mid-day Meal scheme). Additional spending required = Rs 1 lakh crore.

vi) Genuinely implement MGNREGA by spending Rs 3.62 lakh crore as demanded by the NREGA Sangharsh Morcha. Additional spending required = Rs 2.9 lakh crore.

vii) Double government spending on agriculture. Additional spending required = Rs 1.4 lakh crore.

viii) Total = 7.48 + 3.87 + 2.9 + 2 + 1 + 2.9 + 1.4 = Rs 21.55 lakh crore (See Table 22).

After implementing all the above suggestions, the government would still have Rs 6.33 lakh crore to finance many more such proposals.

In demanding of the government that it implement the above suggestions, we are only actually asking the government to implement the dreams of our country’s founding fathers, which are encapsulated in the Directive Principles of the Constitution. They call upon the State to strive to:

- provide good quality education, health care and nutrition to all citizens, and provide all citizens meaningful work and a living wage that ensures them a decent standard of life and full enjoyment of leisure.

References

1. RBI Bulletin, April 2018, https://rbidocs.rbi.org.in.

2. “India’s Covid-19 Pandemic Fiscal Cost Lowest Among Major Nations: Report”, 19 June 2020, https://www.business-standard.com.

3. Sushma Ramachandran, “India Among Most Unequal Countries; 10% Richest Hold 57% of National Income”, Hans News Service, 12 December 2021, https://www.thehansindia.com.

4. See also: Ashish Khetan, “Why India Needs to Rethink its Corporate Tax Cut”, May 14, 2020, https://scroll.in.

5. “What Is Corporate Tax? India’s Corporate Tax Comparison with Other Countries”, 20 September 2019, https://www.newsx.com.

6. There are several articles on this on the internet. See for instance: T.N. Ninan, “Bangladesh at 50 — How it Outpaced India on Many Counts & Justified Break-Away from Pakistan”, 27 March 2021, https://theprint.in.

7. “India Stands out as Poor and Very Unequal, top 1% Owns 33% National Wealth: World Inequality Lab Report”, Newsclick Report, 08 Dec 2021, https://www.newsclick.in.

8. “Two Crore Indians File Returns but Pay Zero Income Tax”, 23 October 2018, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com.

9. Rajul Awasthi, “India’s ‘Billionaire Raj’ Era: Time to Reform Personal Income Tax”, September 20, 2017, https://thewire.in.

10. Our estimate. Budget documents reveal that in 2014–15 and 2015–16, the Modi Government gave tax exemptions to the country’s uber rich totalling Rs 11 lakh crore. For 2016–17, the government changed its methodology of making this calculation to show a much lowered figure—we have calculated that actual tax concession was the same as the previous year, Rs 5.5 lakh crore. In the subsequent years, the government stopped making a full estimate of these tax concessions. Considering the overall attitude of the government towards giving subsidies to the rich, we can safely estimate that tax concessions for the subsequent years must be at least at the same level as the first three years, if not more. So, total tax concessions for 8 years = 5.5 x 8 = Rs 44 lakh crore. For more on this, see our article: Neeraj Jain, “Pandering to Dictates of Global Finance”, Janata Weekly, 19 February 2017, https://www.janataweekly.org.

This calculation done by us matches with a much more rigorous calculation done by economists Reetika Khera and Anmol Somanchi of IIM, Ahmedabad. They have done calculations upto 2019–20, and conclude that the crash in the government estimate of revenue foregone completely disappears if the calculations are redone based on the older methodology, and in fact exceed Rs 6 lakh crore for 2018–19 and 2019–20. (See Figure 1a, Fixing A+B in Reetika Khera and Anmol Somanchi, “A Comparable Series of Tax Revenue Foregone”, May 2020, https://web.iima.ac.in.

11. Vivek Kaul, “Banks have Written Off Bad Loans Worth Rs 10.8 Lakh Crore in Last Eight Years”, 23 July 2021, https://www.newslaundry.com.

12. Sucheta Dalal, “Loan Write Offs Is the ‘Biggest Scandal of the Century’”, 9 May 2016, https://www.moneylife.in.

13. For more on this, see our booklet, “ Is the Government Really Poor?”, Lokayat publication, Pune, 2018, http://lokayat.org.in.

14. Vivek Kaul, “Banks have Written Off Bad Loans Worth Rs 10.8 Lakh Crore in Last Eight Years”, op. cit.

15. “SBI Tops Corporate Loan Waiver List”, 11 October 2019, https://www.dailypioneer.com; Rohit Prasad & Gaurav Gupta,“Data Check: Loan Defaults by Corporates have Cost the State Much More than Farm Loan Waivers”, February 18, 2019, https://scroll.in; Ashish Kajla, “Banks Paying Heavily for Corporate Loan Waivers: RTI”, July 30, 2020, https://www.cenfa.org.

16. Dhananjay Mahapatra, “Now, Modi Govt Too Refuses to Name Foreign Bank Account Holders”, October 18, 2014, http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com.

17. Ashish Mehta, “Surgical Strike? This was Aspirin for Cancer”, November 9, 2016, http://www.governancenow.com; Ritu Sarin, “Exclusive: HSBC Indian List Just Doubled to 1195 Names. Balance: Rs 25420 Cr”, February 9, 2015, http://indianexpress.com; “Panama Papers: From Amitabh Bachchan to Adani’s Brother, Names of 500 Indians Leaked”, April 4, 2016, http://www.business-standard.com; “Exclusive: Panamagate India”, April 8, 2016, http://www.theindianeye.net; “Over 300 Indian Names in New Data Leak That Sheds Light on Offshore Dealings: Report”, 3 October 2021, https://thewire.in.

18. For more on this, see our booklet: “Demonetisation: Yet Another Fraud on the People”, Lokayat publication, January 2017, lokayat.org.in.

19. Dinesh Unnikrishnan, “Finance Bill: Modi Govt Just Made Political Funding More Opaque; Transparency Remains a Promise”, March 23, 2017, https://www.firstpost.com.

20. Martin Hart-Landsberg, “A Wealth Tax: Because that’s Where the Money Is”, 19 November 2019, https://mronline.org.

21. Global Wealth Databook 2021, June 2021, Credit Suisse, Switzerland. We have taken exchange rate as Rs 74 to a dollar, which was the average exchange rate for 2020.

22. “Use Inheritance Tax to Tackle Inequality of Wealth, Says OECD”, 12 April 2018, https://www.theguardian.com; “Inheritance Tax: A Hated Tax but a Fair One”, 23 November 2017, https://www.economist.com; Michael Förster et al., “Trends in Top Incomes and Their Taxation in OECD Countries”, May 2014, https://www.researchgate.net.

23. Neeraj Jain, “For a Universalised Public Distribution System”, Janata Weekly, August 27, 2017, https://janataweekly.org. In this article we have calculated for 2017-18. For the subsequent years, we assume that this would need to be increased by 8% per year.

(Neeraj Jain is an activist with Lokayat and Associate Editor of Janata Weekly.)