Neeraj Jain

Soon after Modi-led BJP won the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, the government felt emboldened to release the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) data, that it had suppressed. The data show that absolute employment in the country has actually fallen during the years of Modi’s prime ministership – the first time it has happened since independence. Soon after, data released by the Central Statistical Office showed that India’s growth rate for Q2 2019 had fallen to its lowest level for the last seven years. But Modi–Shah led BJP government has artfully managed to avoid discussion on the country’s worsening economic and unemployment crisis by channelising the entire discussion in the country around the issue of illegal migrants. The article below discusses the country’s worsening unemployment crisis.

The severity of the unemployment crisis gripping the country can be seen from just a few statistics:

- January 31, 2017: The West Bengal Group–D Recruitment Board invited applications on-line for recruitment of 6,000 Group D personnel in various categories. More than 25 lakh candidates applied for these posts, including graduates, postgraduates and even PhDs. The job required an educational qualification of Class 7 and carried a salary of about Rs 16,000.(1)

- August 30, 2018: Over 93,000 candidates, including 3,700 PHDs holders, 50,000 graduates and 28,000 post-graduates, applied for 62 posts of messengers in UP police. The post requires a minimum eligibility of Class V, and knowledge of how to ride a bicycle.(2)

- November 22, 2019: Nearly 5 lakh graduates, post-graduates, MBA and MCA degree holders applied for 166 Group D vacancies in Bihar’s Vidhan Sabha. The eligibility criteria for the job was that applicants should have cleared Class X. If finally selected, they will work as peons, gardeners, gatekeepers, cleaners, and so on.(3)

Suppressing Data to Hide Unemployment Crisis

Prime Minister Modi has repeatedly asserted that the economy is doing very well and there is no unemployment crisis in the country. In an interview to ANI given on August 11, 2018 (which was bereft of any serious cross questioning, and where vital questions remained unasked), when asked about the present employment scenario in India, he claimed that with the economy growing at a fast pace, with investment into and the pace of execution of infrastructure projects at an all-time high, with FDI inflows at an all time high, with India having emerged as one of the top start-up hubs, with App-based aggregators flourishing in India across innumerable sectors, with foreign and domestic tourism growing, with 3.5 crore first time entrepreneurs being given MUDRA loans – all these initiatives and achievements will obviously be creating many jobs. He in fact claimed that “all this has led to creation of more than one crore jobs only in the last year”.(4) PM Modi repeated this argument while speaking in the Lok Sabha on February 7, 2019. Countering opposition arguments that unemployment in the country was at its highest in 45 years, he claimed during the previous five years, millions of jobs had been created in sectors like the transport sector, the hotel industry, highways construction, new airports, railway stations modernisation and rural and urban housing.(5)

However, employment survey data belie these Modi claims. During the second year of the Modi government, data from the fifth round of the Annual Employment–Unemployment Survey (EUS) conducted by the Ministry of Labour and Employment was released, in September 2016. This report showed that the unemployment rate in India had shot up to a five-year high of 5% in 2015–16. The government panicked, and not only scrapped all subsequent Annual EU surveys, but also the quinqennial Employment–Unemployment Survey conducted by the National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO)—whose next round was due in 2016–17. This survey on employment and unemployment has been conducted regularly every five years since 1972–73 in rural and urban areas, and provides extensive information not just about the levels of labourforce participation rates, work participation rates and unemployment rates, but also on several other indicators of the quality of the workers and the non-workers.(6)

Consequent to the scrapping of these surveys, the government released no official data on the unemployment situation in the country for the next three years. It came in for extensive criticism for scrapping the EU surveys, and so belatedly instituted another employment survey, the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS), to be done by the NSSO. This survey was conducted between July 2017 and June 2018. But with Lok Sabha elections coming, the Modi government decided to withhold the release of this data too, despite the National Statistical Commission (NSC) approving its release—and the NSC is the apex body that coordinates India’s statistical activities and is autonomous. In protest, on January 28, 2019, two members of the National Statistical Commission, including the acting chairman, resigned.(7)

Finally, after the 2019 Lok Sabha elections were done and dusted with, the government released the suppressed PLFS data. The data showed that joblessness was at a 45–year high of 6.1% for 2017–18.(8)

Survey reports of the CMIE (Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy), which are based on a similar sample survey as done by the NSSO, show that including the workers who are unemployed and willing to work but have not been actively looking for a job (generally because of frustration at not getting a job), the unemployment rate (the CMIE calls it Greater Unemployment Rate) was higher than the official figure, at 7% for 2017–18.(9)

Since then, the government has not released any more unemployment data. But data released by the CMIE shows that unemployment has continously been rising, and the Greater Unemployment Rate had risen to 9.35% for Jan–April 2019 and further to 9.94% for May–August 2019.(10) According to the CMIE, the labour force (above age of 15 years) during May–August 2019 was 44.95 crore. An unemployment rate of 9.94% means that nearly 4.5 crore are unemployed.

Manipulating Data

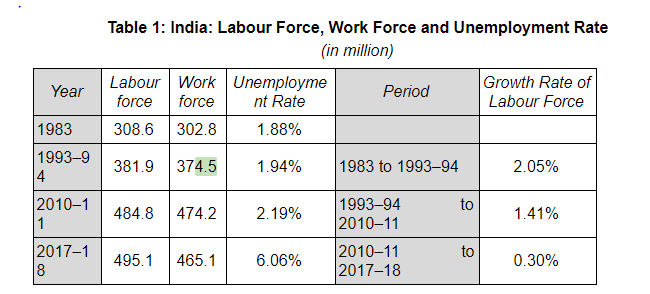

One problem with the official surveys is that its statistics show the labour force to be declining. This artificially reduces unemployment. Note that the number of unemployed is the difference between the labour force and the number of people employed, also called the work force. Therefore, one simple way of reducing unemployment figures without increasing the number of employed is by reducing the labour force. This is precisely what India’s official statisticians have done. According to official figures, over the period 1983 to 1993–94, India’s labour force grew at 2.05% per annum, but during the period 1993–94 to 2010–11, it fell to 1.41%, and then during the period 2010–11 to 2017–18, it fell further to just 0.30% (Table 1).(11) (The CMIE survey also has the same problem. It acknowledges this, but does not analyse it further.)

Let us estimate the labour force in 2017–18 if it had continued to grow at the same rate as during 1983 to 1993–94, that is, at 2.05% per annum instead of 1.41% and 0.30%. In that case, the labour force in 2017–18 would have been 621 million instead of 495.1 million. That means that as many as 126 million people are missing from the labour force.

What can account for the sharp drop in the labour force?

One argument given by mainstream economists is higher enrolment in colleges. This would no doubt reduce the size of the labour force, and enrolment in higher education has indeed increased during the last two decades. The question is, by how much? The All India Survey of Higher Education gives the figures for total enrolment at all levels of higher education, including diploma courses. This survey was first conducted in 2010–11. The AISHE reports for 2010–11 and 2017–18 show that total student enrolment in higher education (enrolment in the regular mode) has gone up from 2.41 crore in 2010–11 to 3.26 crore, that is, an increase of 8.4 million in 7 years. That is a compound annual growth rate of 4.36%.(12) Assuming that enrolment in higher education has grown at the same rate during the earlier years too (the actual growth rate must have been lower), enrolment in higher education for 1993–94 works out to 1.17 crore. That means that total enrolment in higher education has increased by (3.26 – 1.17 =) 2.09 crore over the period 1993–94 to 2017–18. So, of the 12.6 crore people missing from the labour force, only 16.6% is accounted for by increase in enrolment. Even this is much exaggerated, as a significant number of students in higher education want to do jobs, especially those in Arts and Commerce courses. The number of students enrolled in Arts and Commerce courses at the undergraduate level account for 39% of total student enrolment,(13) and it can safely be said that at least half of them are in jobs or wanting to do jobs. In several colleges, especially where poor students study in large numbers, the Arts and Commerce departments are deserted after 10am, as most students have left for doing part time / regular jobs.

Therefore, higher enrolment in colleges does not account for the sharp drop in labour force. The only other reason that plausibly explains the sharp fall in the labour force is that many workers have simply given up looking for jobs out of frustration—because they have not been able to find a job for a long time. They joined the pool of the so-called ‘discouraged workers’. The discouraged workers are not included in the unemployed, nor are they included in the labour force, whereas actually they should be included in both.

Let us now calculate the unemployment rate in 2017–18 including all the discouraged workers in the labour force, as well as in the total number of unemployed. We calculate this as below:

- Total number of missing workers in the labour force over the period 1993–94 to 2017–18 (A) =126 million

- Increase in student enrolment in higher education over the period 1993–94 to 2017–18 (B) = 20.9 million.

- Total number of discouraged workers = A – B = 105 million.

- Total labour force in 2017–18 (C) = 495.1 + 105 = 600.1 million

- Total number of unemployed (D) = 30 + 105 = 135 million

- Unemployment rate, 2017–18 = D/C = 22.5%

That’s almost 4 times the unemployment figure given in the PLFS, and more than three times the CMIE figure.

Since then, as we have pointed out above, CMIE data indicates that the unemployment situation has further worsened.

Youth Unemployment

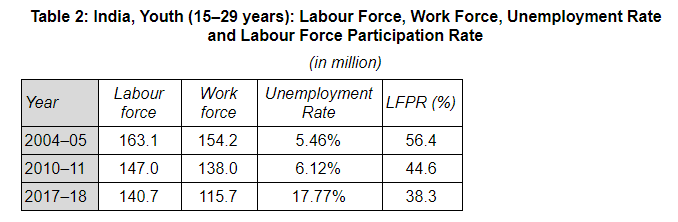

Date made available by the above mentioned official surveys figures show that youth unemployment levels in the country are far worse than the overall unemployment figures. The data are absolutely mind-boggling. Youth unemployment rate in the country has leapt from 5.4% in 2004–05 and 6.1% in 2010–11 to 17.8% in 2017–18 (Table 2).(14) This figure is three times the official overall unemployment rate (6.1% in 2017–18).

That even this high figure is an underestimate is obvious from the sharp fall in Labour Force Participation Rate (LFPR) [LFPR = Total number of people in labour force /total population of that age group]. It has fallen from 56.4% in 2004–05 to 38.3% in 2017–18. Rising student enrolment can only account for a part of this fall, as the fall is very steep. That means, a large section of the youth are falling out of the labour force due to frustration at not being able to get a job. Taking into account the discouraged youth, the youth unemployment level is much higher than 17.8%.

Estimating Real Unemployment Levels in India

Even these high unemployment figures do not capture the full extent of the unemployment crisis gripping the country. That is because whether it be the Labour Bureau survey or the NSSO survey or the CMIE survey, they do not take into account one important aspect of the employment–unemployment problem in India, because of which all these surveys suffer from one fundamental flaw.

And that problem is, that there is no unemployment allowance in India. Therefore, people are forced to take up whatever jobs are available, or do any kind of work to somehow earn something and stay alive—like selling peanuts on bicyles or selling idlis or pani-puri by the roadside or buying some vegetables from the wholesale market and selling them on a cart or collecting scrap from houses. All the above mentioned surveys consider all these people to be ‘gainfully employed’, even if they are not earning enough to eat two full meals a day. Calling these people employed is actually an absurdity—they are all actually unemployed, or underemployed, victims of an economy that is not being able to create decent jobs.

Let us make an estimate of the extent of real unemployment+underemployment in the country.

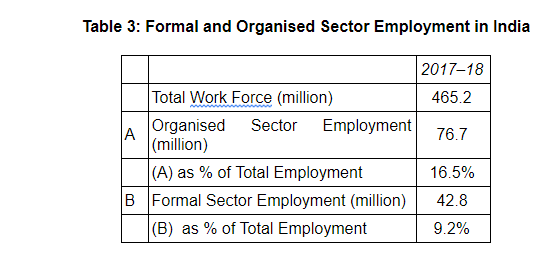

It is generally believed that the only meaningful jobs in the economy are what are called organised sector jobs. The organised sector includes all units with 10 or more workers if using power and 20 or more workers if not using power. It has been estimated from PLFS 2017–18 data that the organised sector accounts for only a small share—16.5%—of the total employment (Table 3).(15)

Taking advantage of the neoliberal economic reforms in the country and the systematic assault on labour rights by the government of India, Indian organised sector firms have adopted a systematic policy of replacing permanent staff with contract or temporary workers, and are also subcontracting out work to smaller units in the informal sector who are able to produce goods at much cheaper rates due to low wage costs. Therefore, not all organised sector jobs are formal jobs, or what the Economic Survey 2015–16 calls ‘good jobs’,(16) where workers have at least some legal rights such as security of employment, minimum wages, sick leave, compensation for work-related injuries and right to organise.

What is the size of the formal / informal workforce in the country? Even the government does not know. The Economic Survey of 2018–19, released on July 4, 2019, says “almost 93%” of the total workforce is ‘informal’. The Survey does not mention the source of this information. While the Niti Aayog’s Strategy for New India at 75, released in November 2018, said: “by some estimates, India’s informal sector employs approximately 85% of all workers”. From where did it get this figure? The Niti Aayog refers to a 2014 report, OECD India Policy Brief: Education and Skills, which, in turn is silent on its source of information.(17)

More recently, the Azim Premji University has published a paper by economists Santosh Mehrotra and Jajati Parida. They base their calculations on PLFS 2017–18 data and estimate that the total formal employment in the country is only 9.2% of the total employment in the country.(18)

Therefore, it can definitely be said that more than 90% of the jobs in the country are informal sector jobs. That’s a stunning figure. Most of the people doing these informal jobs—such as fruit sellers selling a few dozen bananas on hand carts, roadside hawkers selling clothes or other sundry items, graduates running tiny telephone recharge shops or driving autorickshaws for 12 hours every day, sales boys and girls going from house to house selling cosmetics / sarees / books, unorganised sector construction workers working in dangerous conditions at construction sites, farmers toiling day and night in an attempt to extract the maximum possible from their tiny holdings—earn below subsistence wages, earn so little that they are barely able to stay alive.

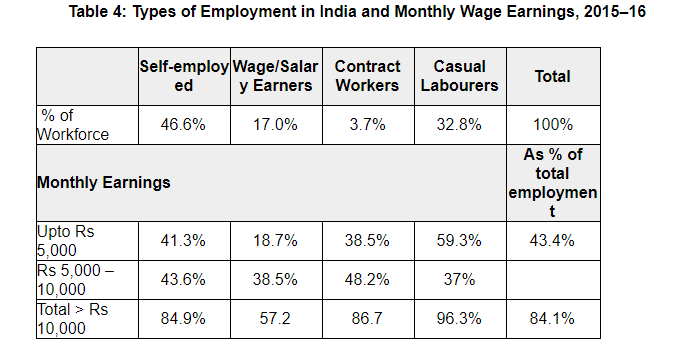

This is borne out by a study based on the Labour Bureau’s Fifth Annual Employment–Unemployment Survey released in September 2016 (Table 4).(19) The study found that of the total workforce in the country, as much as:

- 43.4% of the total workforce earned less than Rs 5,000 per month, and

- 84.1% of the workforce earned less than Rs 10,000 per month.

These are jaw-dropping figures. While they would appear to be unbelievable to our young readers, most of whom are being brought up on a diet of false propaganda about development dished out by the media every day, these figures are similar to another earlier official report of the National Commission for Enterprises in the Unorganised Sector (NCEUS). The government had set up this Commission under the chairmanship of Prof. Arjun Sengupta to advise on issues related to the country’s unorganised workforce. In its study, NCEUS set an overall minimum of Rs 20 per person per day in 2004–05 as its cut-off for defining the ‘poor and vulnerable’. In its report submitted in 2006, the Commission estimated that 77% of Indians earned below this cut-off! Rather than act on the recommendations of this Commission, the government wound it up.(20)

So, to conclude, a large section of the informal sector workers—who earn so abysmally little—should actually be considered as underemployed and included in the unemployed. In the developed countries, people working part-time and desirous of full-time jobs are considered as underemployed and included in the number of unemployed. This is also the spirit of the Directive Principles of the Indian Constitution, which calls upon the State to endeavour to secure for all workers a living wage that ensures a decent standard of life and full enjoyment of leisure and social and cultural opportunities (Article 43).

Therefore, this means that of the 460 million workforce in the country in 2009–10, at least 43% (the number of workers earning below Rs 5000 per month) or even 50% or probably even more should be considered to be underemployed and included in the unemployed. Adding this figure to the number of people officially unemployed, plus the large number of discouraged workers—would make unemployment rate in the country reach stratospheric levels.

Such is the level of unemployment in the country!

Endnotes

- “This State Received 25 Lakh Applications, Including Phds for Posts of Peon and Guard: Shocking!” January 31, 2017, http://indiatoday.intoday.in.

- “Over 93,000 Candidates, Including 3,700 PhD Holders Apply for Peon Job in UP ”, August 30, 2018, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com.

- “Nearly 5 Lakh MBA, BTech, Postgraduates Apply for Group D Jobs in Bihar”, November 22, 2019, https://www.indiatoday.in.

- “PM Modi Counters Opposition on Unemployment, Economy, GST, NRC”, August 11, 2018, https://www.narendramodi.in.

- “Most Unemployment Surveys are Skewed, PM Narendra Modi Tells House”, February 8, 2019, https://www.business-standard.com.

- “Survey Discontinued, Centre Clueless About Unemployment”, March 6, 2018, https://www.dnaindia.com; Sona Mitra, “The Indian Employment–Unemployment Surveys: Why Should it Continue?”, August 13, 2018, http://www.cbgaindia.org; Rosa Abraham, Janaki Shibu and Rajendran Narayanan, “A (Failed) Quest to Obtain India’s Missing Jobs Data”, February 1, 2019, https://thewire.in.

- James Wilson, “Lies, Deceit and Invented Truths in the Modi Regime”, February 10, 2019, https://www.telegraphindia.com; “2 More Members of NSC Quit on Feeling Sidelined”, January 30, 2019, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com.

- “Cat Finally Out of the Bag: Unemployment at 45-Year High, Government Defends Data”, May 31, 2019, https://www.indiatoday.in.

- Mahesh Vyas, “Employment—The Big Picture”, CMIE Working Paper, https://unemploymentinindia.cmie.com.

- “Unemployment in India: A Statistical Profile”, Jan–April 2019 and May–August 2019, CMIE, https://unemploymentinindia.cmie.com.

- Economic Survey, 2001–02, Labour and Employment, Tables 10.6 and 10.7, http://indiabudget.nic.in; Economic Survey, 2013–14, Human Development, Table 13.6, http://indiabudget.nic.in; Santosh Mehrotra and Jajati K. Parida, “India’s Employment Crisis: Rising Education Levels and Falling Non-agricultural Job Growth”, October 2019, CSE Working Paper, https://cse.azimpremjiuniversity.edu.in.

- All India Survey on Higher Education, 2017–18 and 2010–11, Department of Higher Education, MHRD, Government of India, https://mhrd.gov.in.

- All India Survey on Higher Education, 2017–18, ibid.

- Santosh Mehrotra and Jajati K. Parida, op. cit.

- Ibid.

- Economic Survey, 2015–16, Volume 1, p. 140, http://indiabudget.nic.in.

- Prasanna Mohanty , “Labour reforms: No One Knows the Size of India’s Informal Workforce, Not Even the Govt”, July 15, 2019, https://www.businesstoday.in.

- Santosh Mehrotra and Jajati K. Parida, op. cit.

- Vivek Kaul, “Book Excerpt: The Real Story Behind India’s Low Unemployment”, April 19, 2017, https://www.firstpost.com.

- “Why the Poor Do Not Count”, May 30, 2016, https://rupeindia.wordpress.com.