Aseem Shrivastava

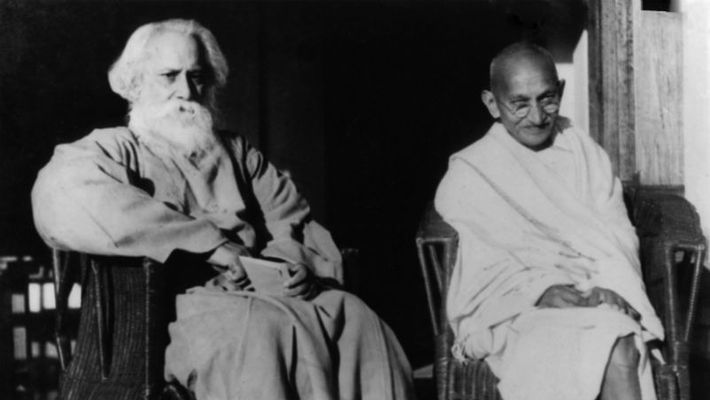

A year in which the country celebrates the Mahatma’s 150th birth anniversary offers us a timely opportunity to consider his criticisms of modernity and juxtapose them with those of the other towering figure of his generation, Rabindranath Tagore, whose 78th death anniversary is on August 7.

Much is made nowadays of the differences between Tagore and Gandhi. It is true that they saw many aspects of the world—especially when it came to the place of politics and certain forms of mass nationalist protest—very differently. Yet, when it came to their view of human life, the fundamentals of their thinking were remarkably coincident. Here are some points on which Gandhi and Tagore thought alike.

Firstly, they both took a civilisational view of the world, and of India’s place in it. This meant that they understood just how different India’s history and culture (primarily rural) were from that of the modern, urbanised West. This informed their trenchant critiques of modernity. While Gandhi (since the days when he wrote Hind Swaraj) saw it as a global pandemic, and was altogether dismissive of it, blaming it for the greatest share of the world’s problems, Tagore’s own assessment was more nuanced, even if his scepticism about the claims made on behalf of progress was inexorable. Importantly, they both saw ‘modernity’ as being an important source of the crises facing humanity. Both Gandhi and Tagore were precise in identifying the central fault with modernity—the fact that it unnecessarily complicated even simple things because of its in-built drive towards power and the multiplication of wants, in the process wasting enormous energy and enthroning money and the machine as cardinal values, ultimately responsible both for the plunder of the natural world as well as the intensified exploitation of working humanity. They both preferred the time-honoured Indian ideal of simplicity to the superficial sophistication of modern European life. In consequence, they were unsparing in their criticism of those of their educated countrymen who, in awe of the West, had lost all confidence in their own traditions and their power to renew themselves.

Secondly, this indictment of modernity was, for both Gandhi and Tagore, rooted in the fact that it was remorselessly materialist and saw humanity only in its physical aspect. Tagore rejected the modern belief which held “the physical body to be the highest truth in man.” For both thinkers (and they were both religious), humanity was fundamentally ‘spiritual’, a notion largely alien to the desacralised modern world. To them, the absence of this realisation is what makes modernity inherently competitive and aggressive, frequently culminating in violence and war.

Thirdly, Gandhi and Tagore shared a very similar perspective when it came to understanding the relationship between the city and the countryside. Gandhi is often accused of idealising villages. We know well that Indian villages—like most other places—are hardly free of structural injustices. Gandhi was quite aware of this. Yet, he felt that true swaraj was not possible unless and until the balance of power between town and country shifts towards the latter. The aggressive urbanisation imposed by modernity would compound problems for people living in both places.

To Tagore, villages constituted the ‘cradle’ of humanity. In his important but widely ignored tract Robbery of the Soil, he wrote about villages that “they are nearer to nature than the towns and are therefore in closer touch with the fountain of life. They have the atmosphere which possesses a natural power of healing . . . The city, in its intense egoism and pride, remains blissfully unconscious of the devastation it is continuously spreading within the village, the source and origin of its own life, health and joy.” These words may well have come from Gandhi.

Fourthly, for both Gandhi and Tagore, society (implying human community), and not the State, is the mainstay of life in India. This is very different from the Western world, where the State constitutes the centre of gravity of human affairs. In Hind Swaraj, Gandhi mocked parliaments as “emblems of slavery”—one reason among many as to why swaraj cannot be crudely translated as ‘democracy’ in English.

Years before Gandhi published his book, Tagore, in a lecture to Congress cadres in Kolkata, spoke of Our Swadeshi Samaj, in which he contrasted India and the West. Unlike in Europe, where society would collapse without the State, in India it is relatively secondary to human welfare, he argued. Both recognised the oppressive features of the modern State, especially in India, where its foundations have always been colonial. The antidote to this was a public life in which the community, rather than the State, would guide human affairs.

Fifth, both put all their faith in the creative renewal of Indian traditions. This was to be achieved significantly through education. Tagore’s vision, as embodied in Shantiniketan, was close enough to Gandhi’s for him to wish to entrust it to his care after his demise. They both had their visions of autonomous self-rule, swaraj. As Ashis Nandy and others have pointed out, they were “critical traditionalists”, who were happy to borrow from the modern world, but only on terms which were uniquely and uncompromisingly Indian. Neither Gandhi nor Tagore (unlike Nehru or Ambedkar), for instance, used the modern language of ‘development’ to frame and understand India’s challenges. For Tagore, the answer to India’s economic challenges lay not in a development imitative of the West, but in “rural reconstruction”, a task which he aimed at (with initial success) in his experiments with village industries and handicrafts in Sriniketan, one of the few practical experiments in swaraj at the grassroots during the last hundred years.

Finally, both Gandhi and Tagore were the earliest harbingers of the planetary ecological crisis, the latter warning of its imminence in multiple literary genres, over 50 years before the Stockholm UN conference in 1972. To Tagore, modernity was characterised by a structural ecological alienation which all but forbade the communion with nature necessary to human freedom. If he were alive today, he would ask for our relationship to the natural world to be resumed, renewed and nourished. Without such a consecration, humanity may not survive long, let alone rediscover its freedom.

(The writer is a faculty member of Ashoka University.)